Reassessing Periyar E.V. Ramasamy’s take on Tamil, which he called a barbarian language Premium

The Hindu

Explore Periyar's controversial views on Tamil as a "barbaric language" and their implications for cultural identity and progress.

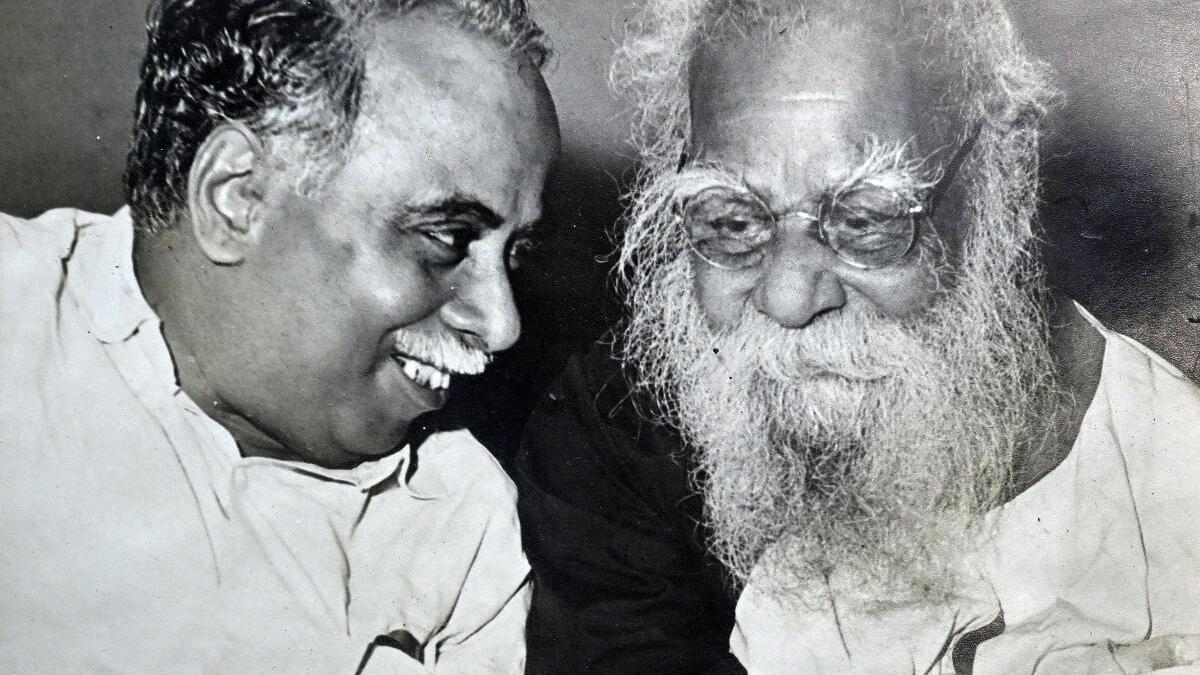

Actor and Makkal Needhi Maiam founder Kamal Haasan’s debut speech in the Rajya Sabha, in which he launched a scathing attack on Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman over her remarks on Dravidar Kazhagam founder Periyar E.V. Ramasamy, has again cast the spotlight on one of Periyar’s most controversial assertions: Tamil is a barbaric language. The Minister had accused DMK leaders of displaying the portrait of a man who had described Tamil in such disparaging terms. Unlike many political figures who reconsider their position in the face of public outcry, Periyar remained resolute and unapologetic. A rationalist who fought for self-respect and firmly believed that Hinduism was inherently casteist, he had little patience for Tamil literary texts that, in one way or another, promoted the idea of God and justified the notion that greatness depends on one’s birth.

He went so far as to pen a detailed exposition defending his characterisation of Tamil, articulating his point with characteristic bluntness. Yet, other than a committed band of Periyarists, none of his ideological heirs was prepared to endorse such a stark view. His political successors — including C.N. Annadurai and M. Karunanidhi — distanced themselves from his position on the Tamil language, the Tirukkural, and the Silappathikaram, though they maintained their distance from the Bhakti literature too.

Karunanidhi, in fact, adopted a markedly different approach. He wrote the dialogues for Poompuhar, the film adaptation of the Silappathikaram, erected a statue of Kannagi on the Marina, assiduously promoted ancient Sangam literature, and penned commentaries on the Tirukkural. The DMK thus charted a distinct course, positioning itself as a custodian and champion of Tamil linguistic pride and cultural legacy. During his tenure as part of the Congress-led UPA, Karunanidhi secured the classical language status for Tamil — a milestone celebrated by his party as historic recognition of the language’s antiquity and literary richness. Since then, the DMK has persistently accused the BJP of failing to accord Tamil financial support commensurate with that extended to Sanskrit, framing the issue as one of cultural equity and federal fairness.

Yet. it was Periyar who advocated reforms to the Tamil script — proposals that were officially accepted when M.G. Ramachandran was the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister. In support of his argument, Periyar cited the script reforms undertaken by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey. “I have been saying for the last forty years that Tamil is a barbaric language. Whenever Brahmins and the Brahmin-dominated government sought to impose Hindi as the national and official language, I made some allowance for Tamil in order to oppose their efforts. Even then, I wrote that English is the language that should take the place of Tamil,” Periyar said while defending his position. Periyar’s views on the Tamil language and literature are examined in The Cambridge Companion to Periyar, edited by A.R. Venkatachalapathy and Karthick Ram Manoharan. In his essay, Periyar’s Engagement with Literature, Antony Arul Valan argues that critics who cite Periyar’s description of Tamil as a barbaric language as evidence of his anti-Tamil sentiment often overlook the broader corpus of his writings, which contextualises his hyperbole and explains the intellectual foundations of his critique.

In their introduction, Venkatachalapathy and Manoharan observe that Periyar believed that the DMK was needlessly glorifying an imagined, pristine and hoary Tamil past, while compromising on the pressing questions of caste and gender. Periyar’s grievance in part was that 99% of the Tamil teachers, in his assessment, lacked even a rudimentary knowledge of English. As a result, they remained insulated from global intellectual currents and perpetuated irrationality. “Tamil teachers have a deep faith in religion that has made them believe in superstition and rendered them dogmatic. They are miles removed from philosophical debate,” he wrote. Another of his arguments was that, until relatively recent times, teachers of other subjects were predominantly Brahmins, which hindered the development of a rational mindset among students. “Even a student learning science smears his forehead with holy ash or Vaishnavite marks,” he quipped.

If he was well disposed towards any text, it was the Tirukkural. Yet, he did not spare even that. His contention was that though Tiruvalluvar castigated what he termed “Aryan barbarism”, he had nevertheless succumbed to certain elements of it. “We can take solace in the fact that the Aryans were more barbaric than the Tamils,” Periyar remarked.