I never expected my stories would appeal to Booker jury: Banu Mushtaq Premium

The Hindu

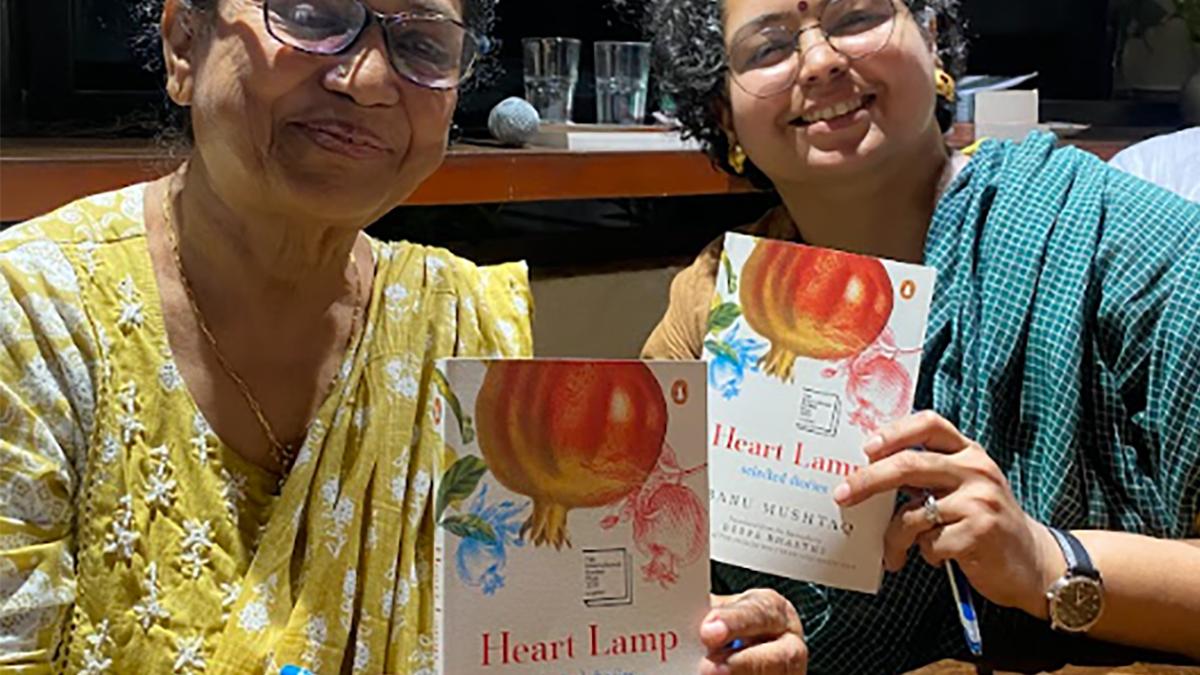

Banu Mushtaq discusses her International Booker-nominated short story collection, Heart Lamp, and the importance of regional representation in literature.

Banu Mushtaq begins by reading aloud a story from her International Booker-nominated short story collection, Heart Lamp, titled “The Arabic Teacher and Gobi Manchuri.” The story is about a lawyer who hires an Arabic teacher, who is very fond of Gobi Manchuri, for her two young daughters, and a series of unexpected events that ensue because of the teacher’s obsession with the cauliflower dish.

The activist, lawyer, and writer, at a recent book discussion at Champaca Bookstore, says, “I just wanted to express in this story about a mother’s duty and compulsion to educate her girl children.”

This “slightly funny story, even with a dark undercurrent,” as writer and editor Kavya Murthy, who moderated the session, puts it, sets the tone for the rest of the evening, as Mushtaq, her translator Deepa Bhasthi, and Murthy discuss the book, its Booker nomination, the stereotypical depiction of Muslim characters in literature and the intricacies of language and translation, among other things.

“The most interesting thing for me as a Kannada speaker is that in this story we are very much in regional Karnataka, in the homes and places that are not frequently talked about,” notes Murthy, before asking Mushtaq, “How important, as a writer, is it for you to make sure that a reader understands where you are located?”

Mushtaq says it isn’t just about where but also about a “glimpse of what you are.” According to her, during the 1980s, there were several social movements such as Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha and Dalita Sangharsha Samiti, and literary movements like the Bandaya Sahitya movement, theatre activism and feminist movements, all of which often coalesced together. “I am a product of those movements,” says Mushtaq, whose hometown, Hassan itself, was one of the centres of such struggles.

As a budding writer, Mushtaq knew that she wanted to write, but “what shall I write?” was a huge question before her. Whose story she wanted to document, and the circumstances surrounding these characters were unknown to her. “I didn’t know how I should frame these characters, and what I wanted to say through these characters.”

In her opinion, other writers such as Fakir Muhammad Katpadi, Sara Aboobacker, and Bolwar Mahammad Kunhi all faced the same critical issue. “Till then, in Kannada literature, Muslim characters were depicted in black and white. Either they were very beautiful, good people, or villainous characters,” says the spry 77-year-old. “There was no grey area. I was just confused.”

After mandating pet dog licensing and microchipping, Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) bids to do the same for cattle to curb stray cattle issues and man-animal conflicts in the streets. The civic body has moved to make it compulsory for cattle owners to obtain licenses for their animals across all zones.