The untapped potential of stem cells in menstrual blood Premium

The Hindu

Discover the potential of menstrual stem cells for treating women's health conditions and regenerative medicine, despite challenges and biases.

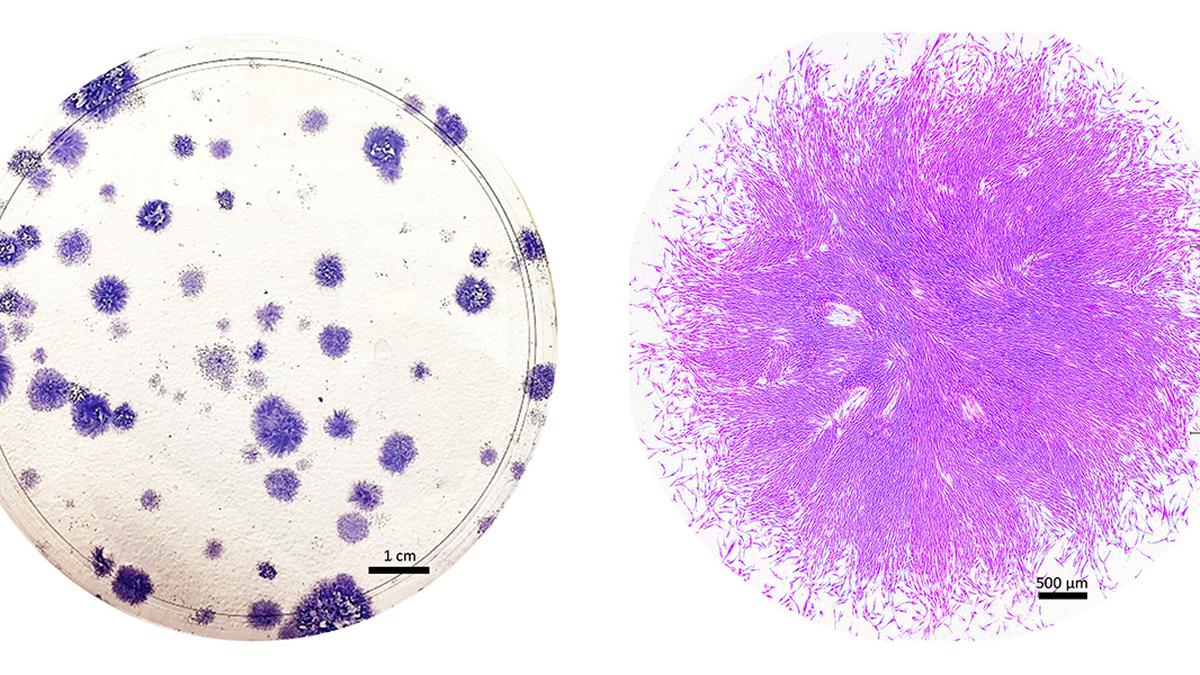

Roughly 20 years ago, a biologist named Caroline Gargett went in search of some remarkable cells in tissue that had been removed during hysterectomy surgeries. The cells came from the endometrium, which lines the inside of the uterus. When Dr. Gargett cultured the cells in a petri dish, they looked like round clumps surrounded by a clear, pink medium. But examining them with a microscope, she saw what she was looking for — two kinds of cells, one flat and roundish, the other elongated and tapered, with whisker-like protrusions.

Dr. Gargett strongly suspected that the cells were adult stem cells — rare, self-renewing cells, some of which can give rise to many different types of tissues. She and other researchers had long hypothesised that the endometrium contained stem cells, given its remarkable capacity to regrow itself each month. The tissue, which provides a site for an embryo to implant during pregnancy and is shed during menstruation, undergoes roughly 400 rounds of shedding and regrowth before a woman reaches menopause. But although scientists had isolated adult stem cells from many other regenerating tissues — including bone marrow, the heart, and muscle — “no one had identified adult stem cells in endometrium,” Dr. Gargett says.

Such cells are highly valued for their potential to repair damaged tissue and treat diseases such as cancer and heart failure. But they exist in low numbers throughout the body, and can be tricky to obtain, requiring surgical biopsy, or extracting bone marrow with a needle. The prospect of a previously untapped source of adult stem cells was thrilling on its own, says Dr. Gargett. And it also raised the exciting possibility of a new approach to long-neglected women’s health conditions such as endometriosis.

Before she could claim that the cells were truly stem cells, Dr. Gargett and her team at Monash University in Australia had to put them through a series of rigorous tests. First, they measured the cells’ ability to proliferate and self-renew, and found that some of them could divide into about 100 cells within a week. They also showed that the cells could indeed differentiate into endometrial tissue, and identified certain tell-tale proteins that are present in other types of stem cells.

Dr. Gargett, who is now also with Australia’s Hudson Institute of Medical Research, and her colleagues went on to characterise several types of self-renewing cells in the endometrium. But only the whiskered cells, called endometrial stromal mesenchymal stem cells, were truly “multipotent,” with the ability to be coaxed into becoming fat cells, bone cells, or even the smooth muscle cells found in organs such as the heart.

Around the same time, two independent research teams made another surprising discovery: Some endometrial stromal mesenchymal stem cells could be found in menstrual blood. Dr. Gargett was surprised that the body would so readily shed its precious stem cells. Since they are so important for the survival and function of organs, she didn’t think the body would “waste” them by shedding them. But she immediately recognised the finding’s significance: Rather than relying on an invasive surgical biopsy to obtain the elusive stem cells she’d identified in the endometrium, she could collect them via menstrual cup.

More detailed studies of the endometrium have since helped to explain how a subset of these precious endometrial stem cells — dubbed menstrual stem cells — end up in menstrual blood. The endometrium has a deeper basal layer that remains intact, and an upper functional layer that sloughs off during menstruation. During a single menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens as it prepares to nourish a fertilised egg, then shrinks as the upper layer sloughs away.

Discover the all-new Kia Seltos 2026 – a refreshed C-SUV that combines premium design, advanced technology, and class-leading comfort. Explore its redesigned exterior with the signature Digital Tiger Face grille, spacious and feature-packed interior, multiple powertrain options including petrol and diesel, refined ride quality, and top-notch safety with Level 2 ADAS. Find out why the new Seltos sets a benchmark in the Indian C-SUV segment.