The multiverse: how we’re tackling the challenges facing the theory

The Hindu

The multiverse is within the realm of scientific possibility. Its existence (or not) is a consequence of the present understanding of the fundamental laws of physics

The idea of a multiverse consisting of “parallel universes” is a popular science fiction trope, recently explored in the Oscar-winning movie Everything Everywhere All At Once. However, it is within the realm of scientific possibility.

It is important to state from the start that the existence (or not) of the multiverse is a consequence of our present understanding of the fundamental laws of physics – it didn’t come from the minds of whimsical physicists reading too many sci-fi books.

There are different versions of the multiverse. The first and perhaps most popular version comes from quantum mechanics, which governs the world of atoms and particles. It suggests a particle can be in many possible states simultaneously – until we measure the system and it picks one. According to one interpretation, all quantum possibilities that we didn’t measure are realised in other universes.

The second version, the cosmological multiverse, arises as a consequence of cosmic inflation. In order to explain the fact that the universe today looks roughly similar everywhere, the physicist Alan Guth proposed in 1981 that the early universe underwent a period of accelerated expansion. During this period of inflation, space was stretched such that the distance between any two points were pushed apart faster than the speed of light.

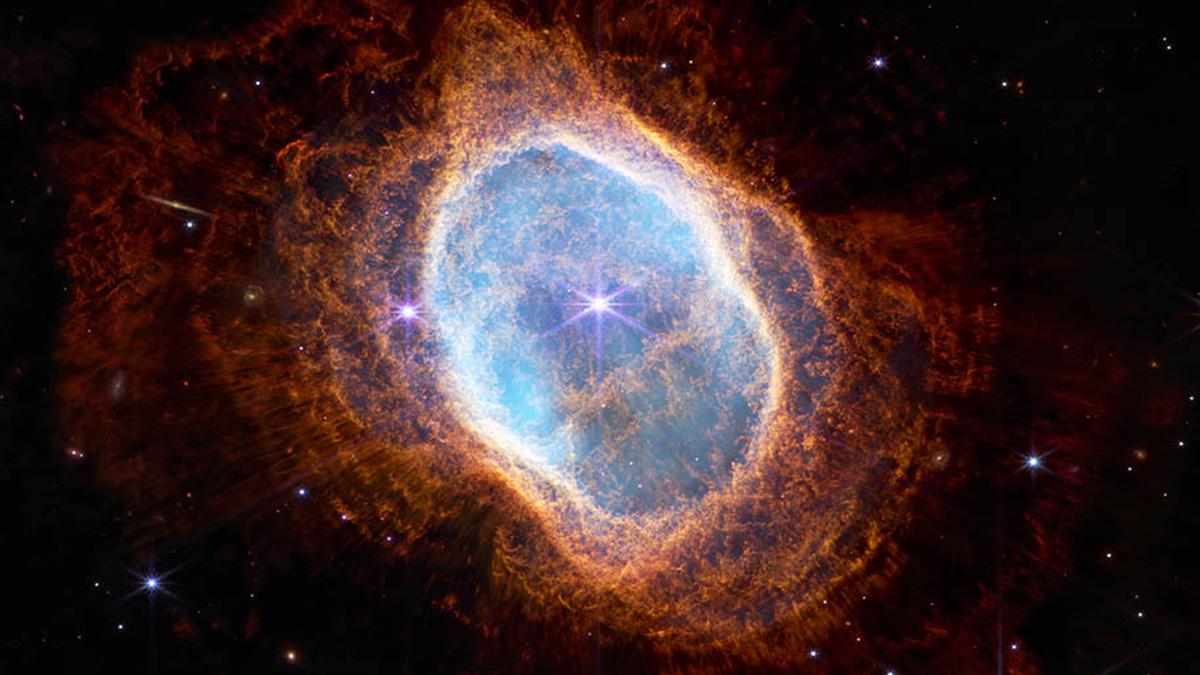

The theory of inflation also predicted the existence of the primordial seeds which grew into cosmological structures such as stars and galaxies. This was triumphantly detected in 2003 by observations of tiny temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, which is the light left over from the Big Bang. It was subsequently measured with exquisite precision by the space experiments WMAP and Planck.

Due to this remarkable success, cosmic inflation is now considered the de facto theory of the early universe by most cosmologists.

But there was a (perhaps unintended) consequence of cosmic inflation. During inflation, space is stretched and smoothed over very large scales – usually much larger than the observable universe. Nevertheless, cosmic inflation must end at some point, else our universe wouldn’t have been able to evolve to what it is today.