How to check if a material is a superconductor – in four steps Premium

The Hindu

Scientists in South Korea have claimed that a material called LK-99 is a room-temperature superconductor. To verify their claim, both they and independent scientists will look for the four characteristic features of the transition to superconductivity: the electronic effect, the magnetic effect, the thermodynamic effect and the spectroscopic effect.

In the last week of July, researchers in South Korea said they had discovered that a material called LK-99 is a room-temperature superconductor. Scientists have been looking for such materials for several decades now for their ability to transport heavy currents without any loss – a property that could revolutionise a variety of industrial and medical applications.

Independent researchers will have to check whether LK-99 is really a room-temperature superconductor before it is accepted as legitimate. When a material becomes a superconductor, the superconducting state will induce four changes in the material. Spot all four and you have yourself a superconductor.

1: Electronic effect – The material will transport an electric current with zero resistance. This is hard to check when the sample of the material is very small, and requires sophisticated equipment.

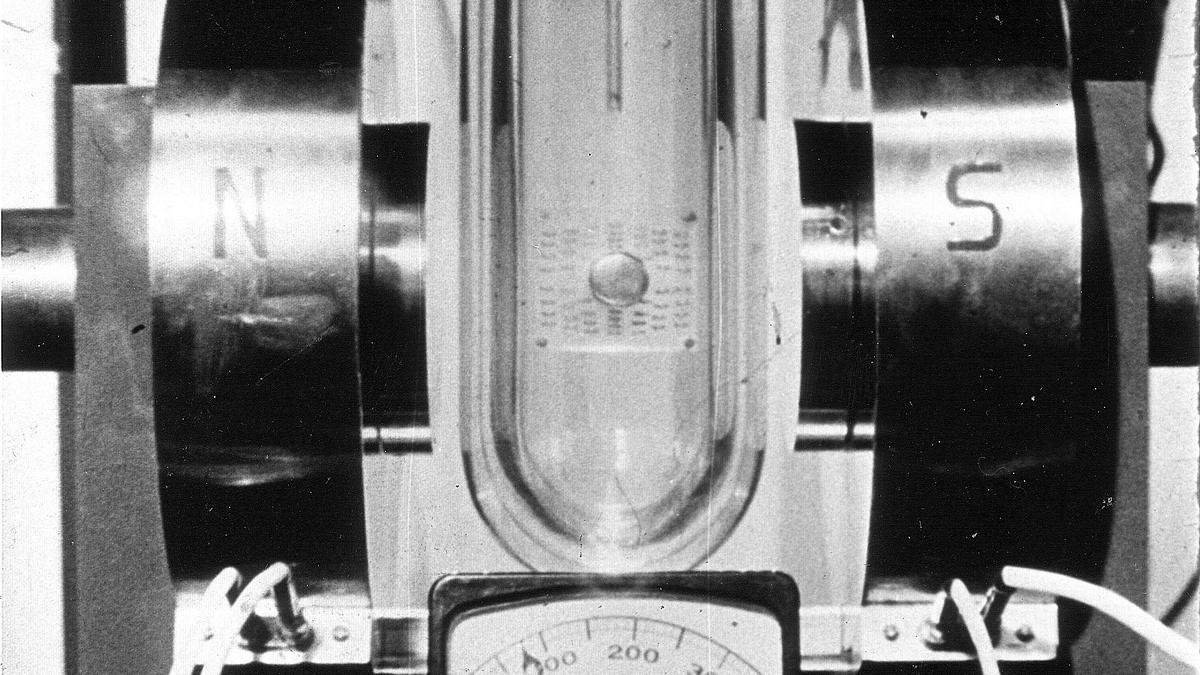

2: Magnetic effect – A type I superconductor (a material that, in the right conditions, becomes a superconductor throughout its bulk) will expel a magnetic field from its body as long as the field strength is below a critical value. This is the Meissner effect: a magnet placed near the material will be pushed away as the material transitions to a superconducting state. A type II superconductor – which transitions through a mix of superconducting and non-superconducting states en route to becoming fully superconducting – won’t expel magnetic fields but will prevent them from moving through its bulk. This phenomenon is called flux pinning. When a flux-pinned superconductor is taken away from a particular part of the magnetic field and put back in, it will snap back to its original relative position.

3: Thermodynamic effect – The electronic specific heat changes drastically at the superconducting transition temperature. The specific heat is the heat required to increase the temperature of the electrons in the material by 1 degree Celsius. As the material transitions to its superconducting state, the electronic specific heat drops. Upon warming the material back up to the critical temperature (below which the material is a superconductor), it jumps back to the value it was when the material was not superconducting.

4: Spectroscopic effect – The electrons in the material are forbidden from attaining certain energy levels, even if they could when the material wasn’t a superconductor. When scientists create a map of all possible energy levels in a superconductor, they should see this as a ‘gap’.

This article is about the two types of conventional superconductors – which are materials whose abilities can be explained using the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer theory of superconductivity. Scientists also know of many unconventional superconductors, but the origin of superconductivity in these materials remains a mystery.