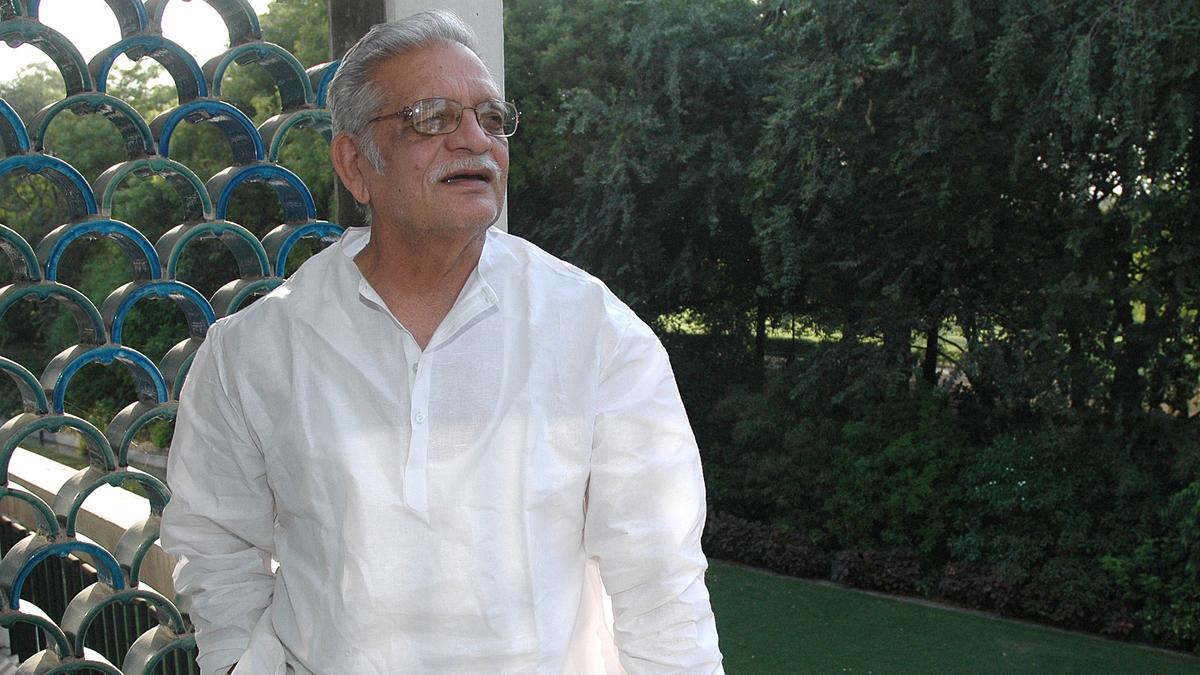

Gulzar, unique and a paradox

The Hindu

Gulzar, a legendary figure in Indian cinema and literature, is celebrated for his poetic prowess and literary contributions.

What can you give a man who already has 22 Filmfare awards, a Grammy, an Oscar, and the Dadasaheb Phalke Award for Lifetime Achievement in Indian cinema? The answer: a Jnanpith award, which is similarly a lifetime achievement award in Indian literature. It was given to Gulzar a few days ago. No person has come even close to winning both these awards before, and that represents both the uniqueness and the paradox of being Gulzar.

Known primarily for his film lyrics, Gulzar has become a part of the emotional landscape of several generations of Indians. But cinema in India is still considered common and low-brow and carries a taint. Gulzar’s cinematic celebrity has thus served to obscure his literary achievement as an Urdu poet of the highest order. His naghme (lyrics) have eclipsed his nazmen (poems), rather as Rahu eclipses the moon. Gulzar himself prizes literature far above cinema. As he once put it, films are like clouds that come and rain and then roll away while literature has a permanent presence, like the blue sky above.

Gulzar’s daring originality as a poet begins with the fact that his staple form of composition is not the ghazal but the nazm. The more popular ghazal is a series of stand-alone couplets linked together only by the clackety-clack rhyme-word, which is a sure-fire applause-catcher. A nazm, in contrast, is a poem on a single theme, which the poet explores at some length. It is often quietly contemplative in tone.

Gulzar has gone further by often renouncing rhyme, which even Faiz and Firaq relied on in their nazms. Crossing another boundary, his unrhymed verse often turns into free verse, as he discards metre too in favour of lines of uneven length. Another feature that makes his poetry cosmopolitan and modern is his penchant for short imagist poems, where the vividly evoked image speaks for itself.

In terms of his themes too, Gulzar has liberated Urdu poetry from its high-rhetorical Indo-Persian conventions and time-worn collocations. His subjects range from the dehumanising mundanity of metropolitan life to cosmic speculations. Each morning, he says in a nazm, he is granted an allowance of a day but by the evening, it has slipped from his pocket or been snatched by someone; the day ends up like a shorn and bleating lamb heading to slaughter.

But nature heals. Gulzar offers us a glimpse of boats with sails fully puffed up, as if holding their breath. We see mountains with their peaks floating among clouds, their feet planted firmly in icy water, and a lofty air about them of solemn stillness. And even higher above are the cosmic bodies. This sun is a dwarf/ It can’t light up each cranny of my being.

Gulzar’s love-poems too are refreshingly different. His lovers are not half-mad adolescents yearning for they know not what; rather, they are adults who have already experienced bittersweet love with multiple unions and separations. I broke off a couple of dry branches from my past/ …You too produced some old and crumpled letters/ With them we lit a fire and warmed our bodies/Stoking up dying embers through the night.