Caste politics in Shivaji’s time that played out in Maharashtra poll and Tamil Nadu Premium

The Hindu

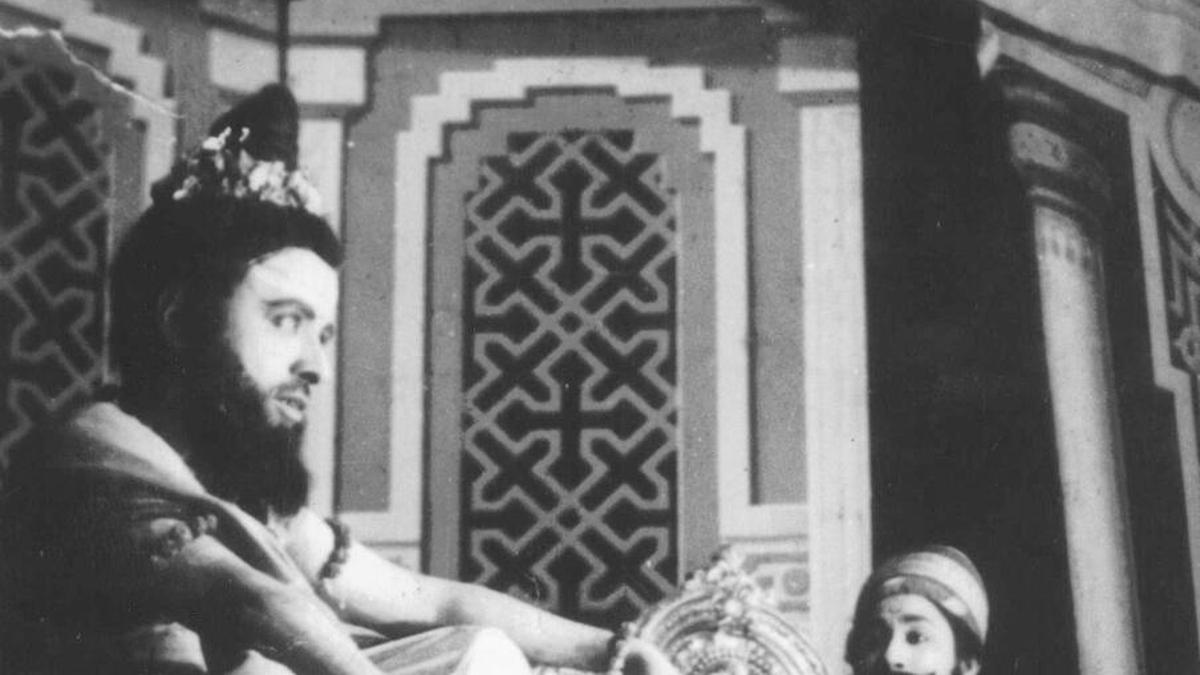

Professor Shraddha Kumbhojkar discusses the political implications of Shivaji's coronation in a Tamil play by C.N. Annadurai.

Shraddha Kumbhojkar, professor and head of the department of history at the Savitribhai Phule University in Pune, recalls Raj Thackeray, nephew of Shiv Sena founder Bal Thackeray, asking NCP (Sharadchandra Pawar) leader Sharad Pawar, who would be that one person whom all Maharashtrians will accept and like. Mr. Raj was hinting that Mr. Pawar was that person, only to be told by the latter that it was Chhatrapati Shivaji. Just as Mr. Pawar had said, diverse political forces and caste groups in Maharashtra swear by Shivaji today, which was evident during the recent Maharashtra Assembly election.

The caste equations in Maharashtra and how Shivaji sought and obtained Brahmin approval for his coronation were the subjects of a Tamil play two years before Independence. ShivajiKanda Hindu Rajyam was DMK founder C.N. Annadurai’s play that asked how and why Brahmins could have the right of refusal over a brave warrior, who had heroically obtained independence for his people from the Mughals, being crowned as the king of the Maratha Empire.

Anna’s intent was clear: He was conveying a political message to Tamils. Incidentally, the Marathi Brahmins of Shivaji’s time spoke contemporary Tamil Brahmin lingo in his play. The play’s plot is a set of events leading to the coronation that some Brahmins oppose since Shivaji is a Shudra, a farmer. A devoted Brahmin follower of Shivaji, Moropant (Pingale) opposes the coronation because of caste reasons. But Chitnis, an upper caste Kayastha, is steadfast and comes up with a plan to seek the approval of Gaga Bhatt, a Brahmin in Varanasi. The Maharashtra Brahmins assure him that if Bhatt approves, they would too.

At first, Bhatt demurs. Then, he agrees, seeing the possibility of Brahmin hegemony being retained, since it would show even the highly popular and respected Shivaji wants their sanction. Bhatt extracts a heavy price — money, jewellery from thulabaram, a month-long feast for Brahmins, and so on. Moropant convinces Bhatt against crowning Shivaji, saying Shivaji will then create a dynasty of Shudras. Bhatt then comes up with a crooked ploy and tells Chitnis he will crown Chitnis instead of Shivaji. This angers the loyal Chitnis. Seeing Chitnis’ absolute and fierce devotion, Bhatt again flip-flops in Shivaji’s favour, although not wholeheartedly.

Parimal Maya Sudhakar, associate professor at the MIT World Peace University, says that according to folklore, Bhatt would only go as far as to put the tilak on Shivaji’s forehead with his foot, not with his fingers, during the coronation.

Prof. Kumbhojkar says there is no record of Moropant being against Shivaji’s coronation although Chitnis did have a grudge against the Brahmins for denying his request to perform upanayanam for his sons. Chitnis, being a prabhu, a kayastha, put himself on the same level as Brahmins, only to be shown his “true” station by them, she adds. Chandramohan, a loyal soldier of Shivaji, doesn’t acquiesce until the very end. He advocates not seeking Brahmin approval. He asks how during a fierce drought could Shivaji agree to organise a feast for Brahmins. Shivaji banishes the recalcitrant Chandramohan from the kingdom as a loving reprimand, explaining that at a critical juncture he couldn’t afford Brahmins stirring up trouble against him.

Shivaji Kanda Hindu Rajyam has an ‘a.k.a’. Its alternative title is Chandramohan, a Shivaji-era Periyarist who was the real hero of the play.