Veteran writer Javed Siddiqui on Satyajit Ray’s unique approach to filmmaking

The Hindu

Javed Siddiqui's journey from journalism to creative writing, working with legends like Satyajit Ray and Yash Chopra.

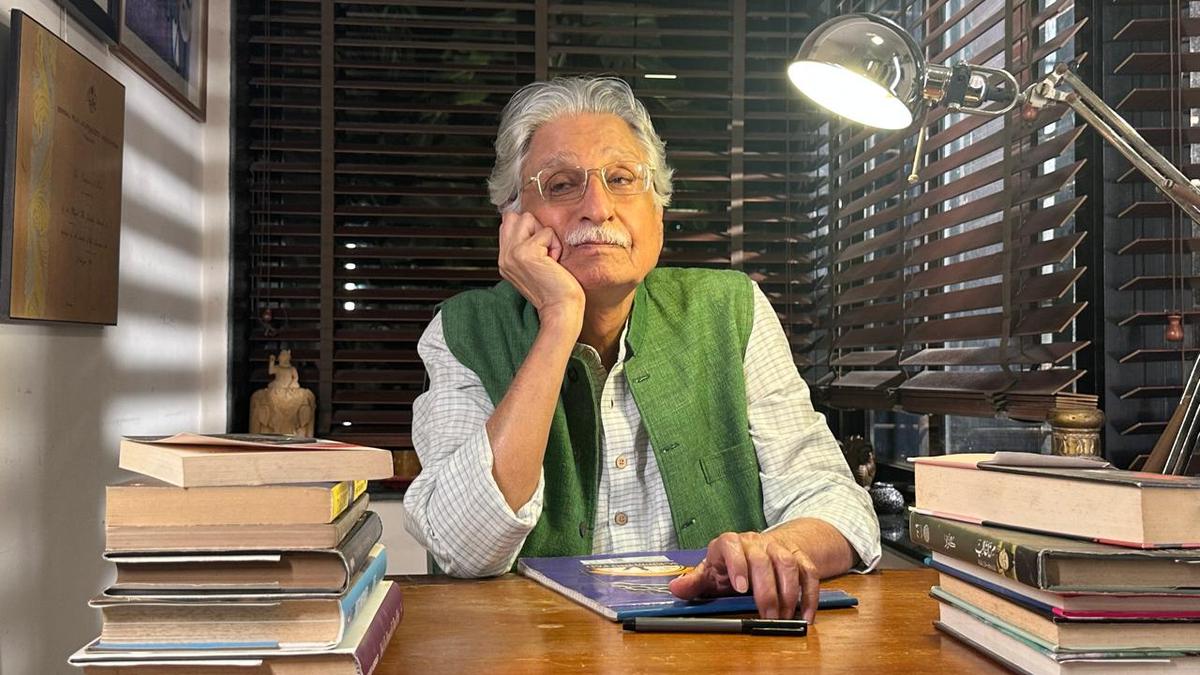

“Kya shakhs tha Ray (What a man Ray was),” says Siddiqui sitting in the study of his house in Mumbai’s Char Bangla area. Once a hub of activity, his study was where creative minds such as M.F. Husain and Yash Chopra met and spent hours.

Siddiqui, who left journalism during the Emergency to follow his passion for creative writing, has seen 83 summers, but his eyes light up like a youngster at the mention of Satyajit Ray. The legendary filmmaker introduced Siddiqui to cinema with Shatranj Ke Khiladi in 1977.

Ray had committed to producer Suresh Jindal to make a Hindi film. But he wanted a story that had its roots in the North, “He didn’t want to adapt a Bangla story as was the norm those days,” recalls Siddiqui. An admirer of Premchand’s writing, initially, Ray wanted to adapt Kafan, but when he came to know that Mrinal Sen had already decided to turn the short story into a Telugu film, he turned his focus to Shatranj Ke Khiladi. “After writing the screenplay, Manik da was looking for someone from a non-film background with an understanding of Lucknawi Urdu of the 1850s. Shama Zaidi, who was doing the costumes knew me because of our Rampur background and suggested my name to him. Ray was a towering figure, literally and metaphorically, for a newcomer it could be overwhelming, but my journalism background prepared me not to be overawed.”

Siddiqui formed a formidable team with Zaidi. “I verbalised the dialogues, and if she approved them, she would nod and type them in Roman on her Remington typewriter, as Manik da didn’t know Hindi and Urdu.” Once Siddiqui asked Ray if he knew any Hindi words, he replied, “Just one: bas (enough).”

As Ray had created Lucknow in Kolkata, Siddiqui says, he needed someone to check the cultural authenticity. “He wanted me to help his Bengali crew with the Urdu dialogues. That’s how I became his special assistant.”

“I haven’t seen a more meticulous director than Ray. He had a red book that he called khata, much like the logbook of a trader. Everyday, when he entered the set, he would sketch every shot in the Khata, accompanied by the Urdu dialogue written in Bengali and its English translation.” For the scene where the East India Company forces enter Lucknow, Siddiqui reveals Ray sketched on an art paper the order in which the cavalry, elephantry, and infantry would move. It became our guidebook at the location.” Siddiqui has preserved that paper as a memento, and it shines on the wall of his study.

Siddiqui went on to pen the dialogues of Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan. Comparing the Awadh of Ray with that of Ali, Siddiqui says that while the latter had an emotional connection with the city, Ray had an objective approach. “He wanted to highlight how the upper middle class remained oblivious and indifferent to the British manoeuvres to seize control. The film remains relevant because the upper middle class’ indifference to politics remains.” He mentions the scene where the chess players are told how the British have tinkered with the rules of the game such as Wazir being called the Queen’. “Here, Ray used chess to underline the political context.”