Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere has the biopic disease

CBC

Bruce Springsteen is sad.

My mistake; Bruce Springsteen was sad. Or to be specific, Bruce Springsteen was sad during the making of his 1982 album, Nebraska. And if we’re to believe the heavy-handed final title cards, he’s still sad today. But it’s a different flavour of sad — a sad managed by therapists, indefatigably supportive friends and a quiet acceptance of his sort-of-abusive, mostly-meant-well father.

This is the focus of Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, a microcosm of an artist’s career helpfully scored by subsequent hits like I’m on Fire and Born in the U.S.A. Attempting less to outline a grand, arcing trajectory, it is a mostly self-contained effort; meticulously cataloguing the writing and recording of that record, and how it changed Springsteen's outlook.

If that nearly flat character arc seems like a shallow hook to hang an entire movie’s hat on, well, how dare you? If you weren’t aware, this is the biopic business: a titanic book and movie industry that operates around two fundamental axioms. One, that if you’ve been famous for long enough, you're also interesting enough to warrant a title with your name in it.

And two, how honest that production ends up being is entirely up to the subject.

This is not to say memoirs, autobiographies or the occasional authorized biography are inherently misleading. For those with the talent — and a pervasive, perhaps self-destructive inclination toward introspection — tell-alls can tell quite a lot. Likewise, in Deliver Me From Nowhere, we do see pathos drudged up from Springsteen’s destructive relationship with intimacy.

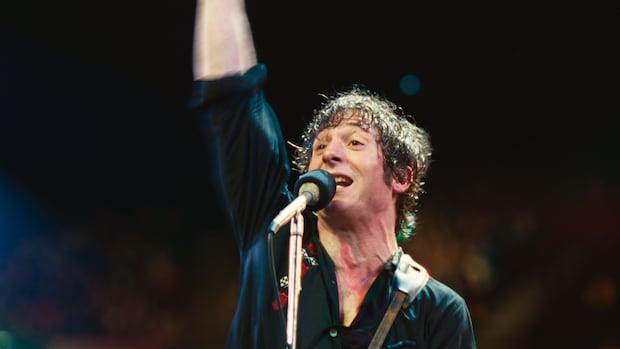

As the Boss (played here by The Bear’s Jeremy Allen White) rides the early-career highs that his rocking album The River visited on the world, we look both backward and forward on his journey.

Ahead of him are the promises of the next level: graduating from up-and-comer on the cusp of superstardom to an actual household name. And from his cow-eyed, almost sweat-inducingly warm manager and co-producer Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong), we are constantly hit over the head with what that step would mean.

Again and again, kindly and continually, like a muppet hammering a felt nail, Landau reiterates how hard all this is for Bruce. To his wife, Barbara Landau; to the know-nothing studio suits; to Springsteen himself (and by extension, always to the audience), he whisper-talks about how his friend doesn’t have it easy.

Despite his inviting, lopsided smile and the casually cool way he sits in diner booths with an arm thrown over the back, Springsteen is dealing with some serious stuff. There’s a storm in his mind, and success — and by extension, leaving his hometown for the big, busy city — isn’t so simple.

As the movie winds on, we’re treated to the possible reasons for that. In sporadic, monotone flashes to Springsteen’s past, we see the moments that shaped him as a child, where he's played by Matthew Anthony Pellicano Jr.

There is the obvious protectiveness Springsteen built for his mother, played here with touching sincerity by Gaby Hoffmann. Underscoring the delicate connection and fierce love between mother and son, we watch a black-and-white scene in which they dance to old records in their living room. And if I had a nickel for every time Hoffman did exactly that (as she did in her performance as the frenetic mother in C’mon C’mon) I’d now have two nickels. Which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it happened twice.

But most importantly, there’s Springsteen’s complicated relationship with his father (Stephen Graham) that's straight out of The Shining. It's not hard to connect the dots to see how a father slapping his son, then congratulating him for fighting back with a baseball bat as he screams at the mother, could do a number on a kid's head.

But there is a fine line when it comes to the usefulness of subtlety: Before that line is mature reservedness, and after comes hollow gesturing. This film steps over the line.