Mapping places where women hung out in Bengaluru’s Cantonment area Premium

The Hindu

But the Bengaluru-based writer and teacher, an assistant professor at St. Joseph’s University, did not just stumble upon Nair’s term serendipitously. “I was initially reading Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak by Madhumita Dutta, and was talking to my dean, Dr. Arul Mani, about the book,” she says. “It was he who suggested I read Janaki Nair.”

It was while reading historian and writer Janaki Nair’s book, The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore’s Twentieth Century, that Nikhita Thomas first encountered an interesting expression: kineticization, “a phenomenon in the 80s and early 90s where there was an increased presence of women in the public sphere due to the popularity of the Kinetic Honda.”

But the Bengaluru-based writer and teacher, an assistant professor at St. Joseph’s University, did not just stumble upon Nair’s term serendipitously. “I was initially reading Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak by Madhumita Dutta, and was talking to my dean, Dr. Arul Mani, about the book,” she says. “It was he who suggested I read Janaki Nair.”

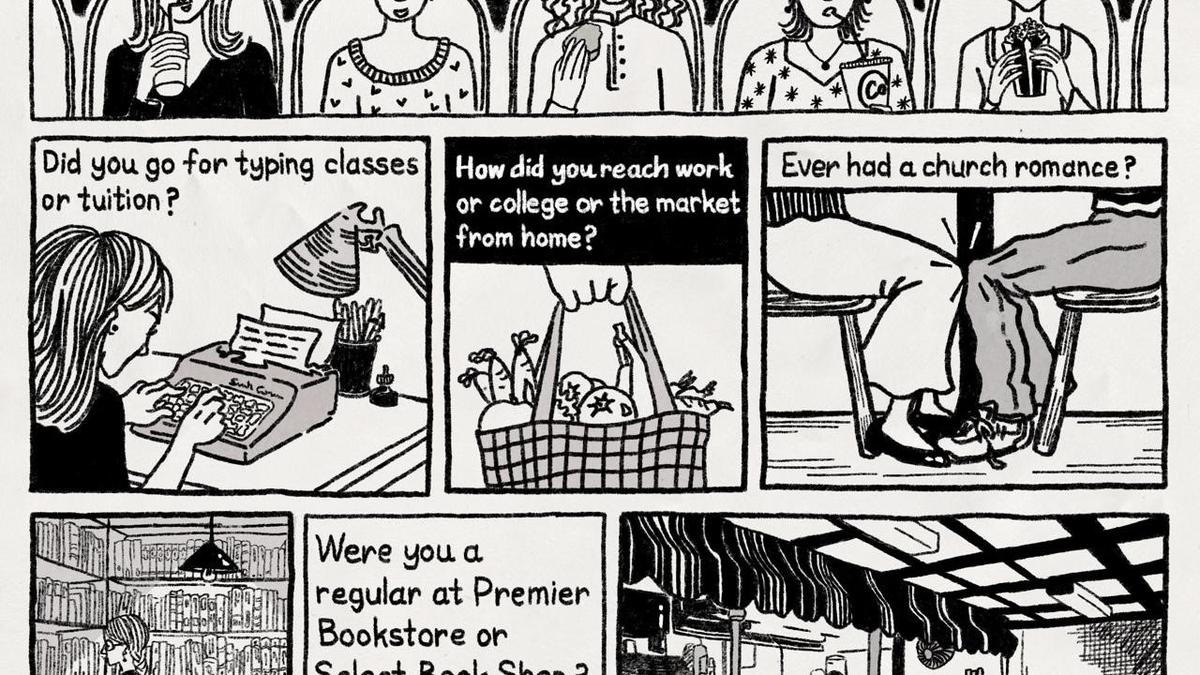

The growing participation of women in public life got her thinking about how the phenomenon of just hanging out transpires for women, says Nikhita, who, along with Pranav V.S., has embarked on a project to map places where women hung out in the city’s Cantonment area between 1984 and 1994. “The idea was to talk to women who lived, studied and worked in Bengaluru Cantonment during the 80s and the 90s,” she says. “We picked this specific period because of the “kineticization” that Janaki Nair talks about and because this was a period of rapid change in the country, including two waves of liberalisation.”

This project, supported by the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) under its Neighbourhood Engagements of Project 560, “seeks to explore the spatial relationships women have with the cities and neighbourhoods they call home,” states the IFA website, adding that Nikhita’s and Pranav’s research engages with the following questions: When are women rendered invisible, and when are they on display in the city? How does the purpose of their movement through the city get women tossed between obscurity/safety, and visibility/danger? And how can spaces designated for one kind of interaction be persuaded to house other exchanges, given the spatial practices of women?

Nikhita first applied for an IFA grant in 2023, wanting to look at student migrants in the city and the spaces they occupied, “specifically to go into their hostel or PG rooms and draw from that,” she says. While she cleared the first round of the grant, she didn’t make it to the final round, “but they encouraged me to apply again.”

In July 2024, Pranav, too, joined the English Department at St. Joseph’s University. They were in conversation with Dr. Mani, she says, who encouraged them to apply for the grant together this time. “We were bouncing ideas off each other, with Pranav initially suggesting we do something about the lakes that used to exist in Bengaluru,” she says.

Dr. Mani, however, was not enthusiastic about this idea, recalls Nikhita, who, around the same time, was also reading the Janaki Nair book. There was also a movie that both of them liked, Brahman Naman, “a movie about the quizzing culture in Bangalore with mostly boys who loiter about the city,” she says. “It is a super movie, but it left us wondering: Where are all the women?”