A tribute to M.S. Swaminathan, ‘the man who fed India’ Premium

The Hindu

Some lessons from M.S. Swaminathan in his experience as a scientist in India which have relevance for the future of research and agriculture in the country

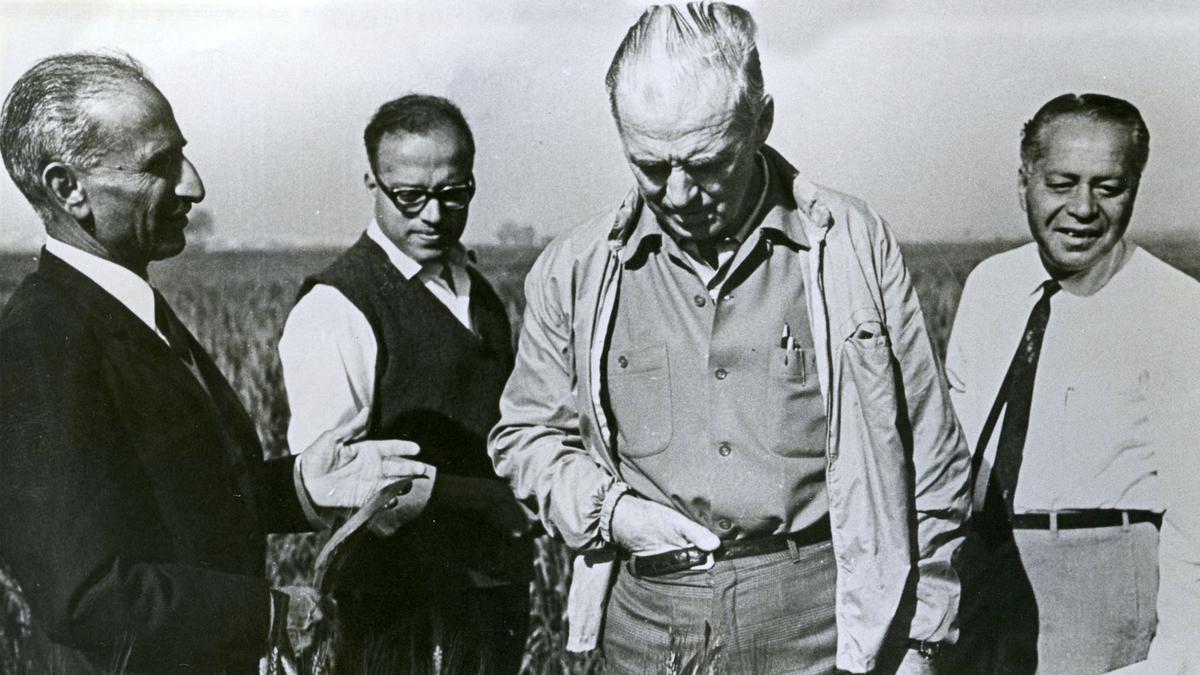

The next step was to subject the seeds to trials on the fields of actual farmers. Swaminathan could not get the Ministry to fund the effort. Fortunately, Lal Bahadur Shastri, who became Prime Minister in 1964, wanted to give higher priority to agriculture and for this purpose appointed C. Subramaniam as Minister of Agriculture. This made a critical difference. Subramaniam called about 20 agricultural scientists for a meeting to hear their views on how to increase food production. When Swaminathan was asked to speak, he frankly told the Minister that he had identified the new seeds that would solve the problem, but the Ministry was unable to fund the necessary trials. Subramaniam promptly called for the file and ensured that the funds were provided. It is a pity that we have no record of what the other scientists said in the meeting, and in particular whether the more senior scientists (Swaminathan was then only 39) had a different view.

This yields the second important lesson. In dealing with complex technical issues, the political leadership must hear the scientists/technical people involved directly instead of relying on the generalist bureaucracy to convey their views. Swaminathan greatly admired Pandit Nehru’s commitment to science, but the book brings out that he soon realised that this “had few takers even in his own government, ministries and the bureaucracy”. On page 48 the author puts it bluntly: “Most ministers barely supported, understood, or believed in research and development…. this was also true of the Agriculture Minister in 1958.. (who ) would order scientists like Swaminathan to go into the field and ‘sort out the problems’ without really understanding the ground realities.”

One of the reasons China has done so well on the economic and technical front is that Ministers are usually technically qualified people, often engineers with a track record of successful management. Subramaniam exemplified that type of political leader: he was a physics graduate and had a good knowledge of science. If we want to achieve Viksit Bharat, and explore new and increasingly complex areas of science, we will need many more such Ministers in the years ahead, not only at the Centre but also in the States.

The field trials were a great success and the next step was to roll out the Green Revolution across the country. This required importing 18,000 tonnes of seed — the largest seed shipment in history — costing ₹5 crore in foreign exchange. There were objections from many fronts. The Finance Ministry was not happy releasing that much foreign exchange. The Planning Commission opposed the proposal on the grounds that it did not believe that the new seeds would do better than what we already had. The Left also opposed the move because the seeds were developed under a grant from a U.S. institution (the Rockefeller Foundation).

Shastri was understandably concerned about these conflicting views. Fortunately, Swaminathan persuaded him to visit the IARI to see for himself how the new wheat was doing. Shastri was convinced and the import of new seeds was duly approved. Tragically, Shastri passed away in January 1966 but Indira Gandhi, who took over as the next Prime Minister, also gave Swaminathan full backing.

The lesson is that when dealing with new and untried ideas, there will always be conflicting opinions even among so-called experts. It is important that all the different points of view are appropriately aired and considered. However, this process may not always result in a consensus. In such a situation, a decision has to be taken at the highest level. Once taken, the thing to do is to back the effort fully. But it must also be subjected to truly independent monitoring, with course corrections.

In the case of the Green Revolution, the results were amply evident within a few years. We reaped a bounteous wheat harvest in 1968 and we were able to start phasing out PL 480 imports. Over time, new problems arose. The excessive dependence on water and also fertilizer use led to environmental problems. Swaminathan himself, having left the government by then, warned about the corrections needed to make the Green Revolution environmentally sustainable. It is a pity that we are yet to implement these corrections.