Why are cyclones in the Arabian Sea so uncommon? Premium

The Hindu

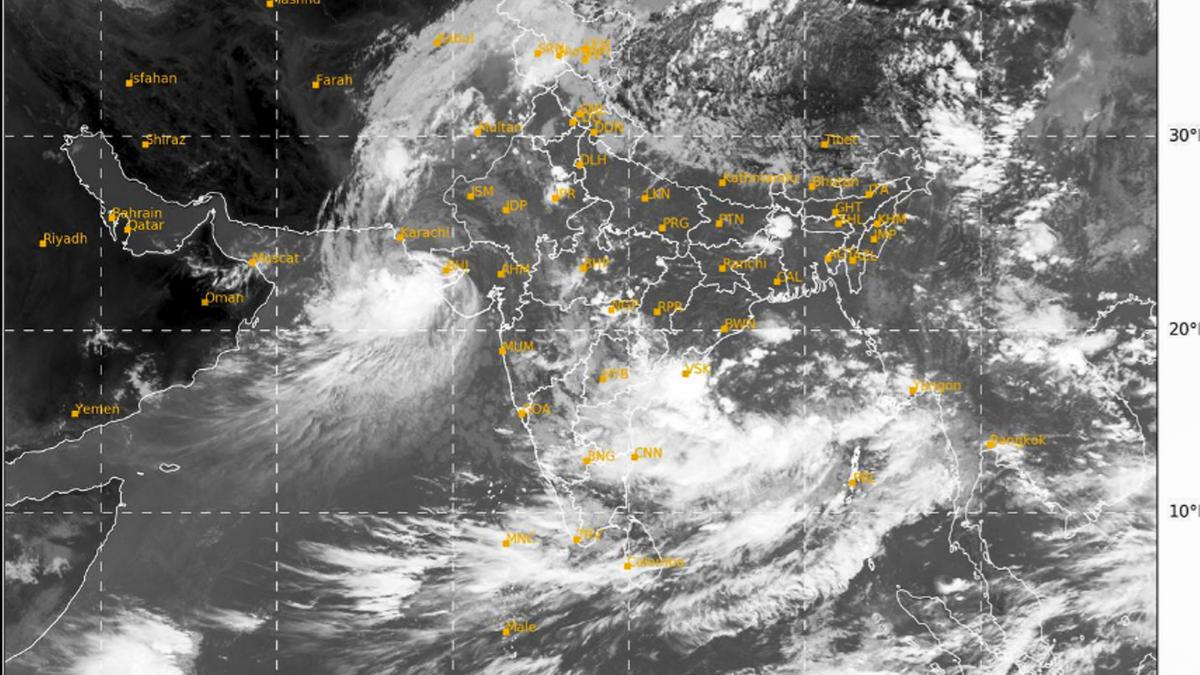

A rare August cyclone, named ‘Asna’, currently lying off the Kutch coast is more unusual for being land-born. Prof. Raghu Murtugudde explains how it took shape and why cyclones are so uncommon in the Arabian Sea.

The North Indian Ocean supplies a large part of the moisture required to generate the 200 lakh crore or so buckets of water during the summer monsoon. That implies a lot of evaporation from the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, which requires these seas to be warm enough to allow evaporation. This is why warm tropical oceans also tend to lend themselves lots of cyclones.

And yet, the North Indian Ocean is the least active region of the world’s oceans vis-à-vis the number of cyclones. The combination of some factors that favour cyclogenesis and some that suppress it make this area unusual in terms of cyclone seasons, numbers, and the response of the ocean and the cyclones to global warming.

The Indian Ocean receives a lot of attention for its monsoonal circulation and the dramatic seasonal wind reversals to the north of the equator. But it’s also unique because it has ‘oceanic tunnels’ connecting it to the Pacific Ocean and the Southern Ocean. The Pacific tunnel brings a significant amount of warm water every year in the upper 500 m while the Southern Ocean tunnel brings in cooler waters under about 1 km.

The Arabian Sea warms rapidly during the pre-monsoon season as the Sun crosses over to the Northern Hemisphere. The Bay of Bengal is relatively warmer than the Arabian Sea but warms further and begins to produce atmospheric convection and rainfall. The trough that eventually leads to the monsoon onset over Kerala arrives in mid-May itself over the Bay of Bengal.

The post-monsoon season is the northeast monsoon season for India, and produces significant amounts of rain over several states.

All these wind patterns and sea surface temperatures influence cyclogenesis throughout the year over the North Indian Ocean and sustain the stark contrast in cyclogenesis between the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

Climate change amplifies the uniqueness of the Indian Ocean. More heat is coming in from the Pacific Ocean now while the Southern Ocean also is pushing in warmer waters. The Indian Ocean is warming rapidly due to these inputs, plus atmospheric changes in winds and humidity.

“I’ve never even been to these places before,” she laughed, “and suddenly I have memories in all of them.” The dates, she added, were genuinely good — long walks, easy conversations, and meals that stretched late into the evening — and the best part was that none of it felt heavy. The boys she met are all planning to visit her in Mumbai soon, not under without any pressure but with a sense of pleasant continuity. “I’m great,” she said, and she meant it.