Thinking of eating bugs to save the planet? Tribal communities in India have been doing it for centuries Premium

The Hindu

The edible insects market is set to grow to $6.3 billion by 2030, according to a study

In a city renowned for its food, Mexican chef Alejandro Ruiz Olmedo shines extra bright. He is a sort of culinary ambassador for Oaxaca and his restaurant Casa Oaxaca has been on the 50 Best Restaurants in Mexico list three years in a row.

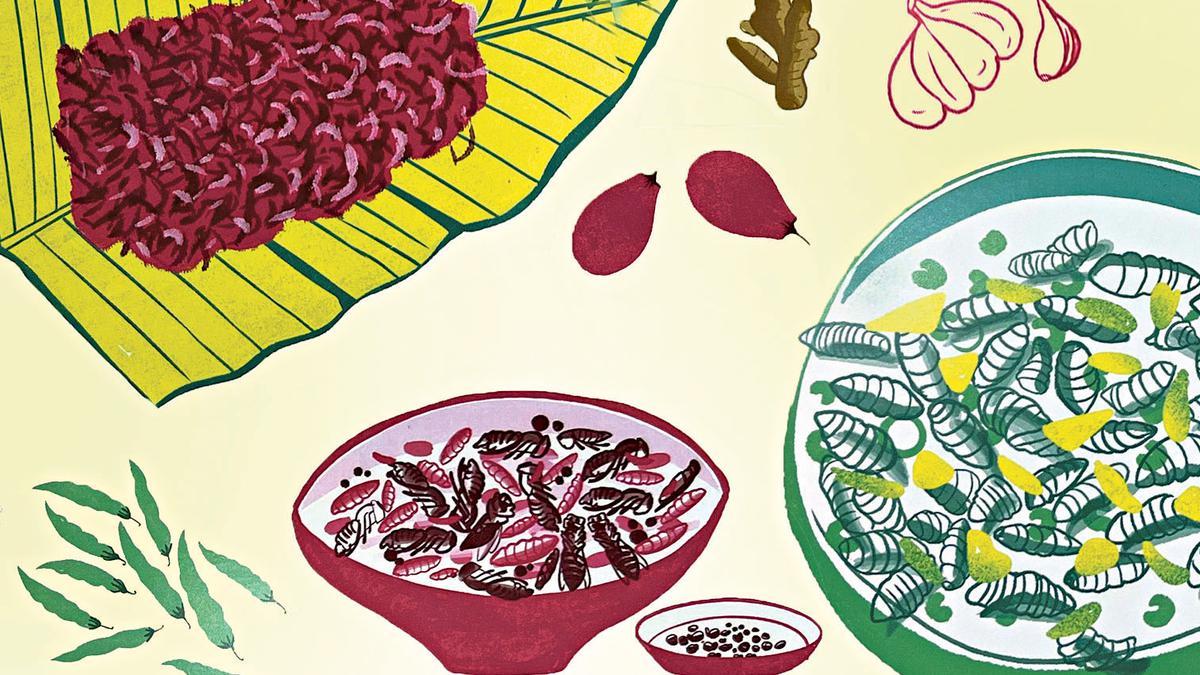

Every dish is a work of art and the tostada I order is no exception. It looks like a garden exploding with deep reds, spring greens and chocolate browns. Except this is no ordinary tostada. It is a tostada de insectos, a crisp corn shell topped with chicatana ants, chapuline grasshoppers and agave worms around swirls of guacamole and herbs.

It is crunchy, and savoury with little sour notes from the ants. And it pairs wonderfully with a mezcal sour cocktail.

“That’s very brave of you,” says a local. There is indeed always an element of daring and adventure when eating bugs. Insects are slowly becoming haute cuisine, proudly part of the menu at upscale restaurants like Casa Oaxaca. The salsa freshly made at the table comes with the option of ground-up chapuline grasshoppers.

With human population estimated to touch 9.8 billion by 2050, we are told we cannot continue eating beef, mutton and chicken the way we do. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) says we all need to eat more bugs to meet our protein needs. The European Union has okayed powdered migratory locusts and dried mealworms as food. Eating insects isn’t just for Instagram likes, it’s sort of an ecological badge of honour. Conquer your gag reflex and save the planet. Barclays estimates the edible insects market will grow to $6.3 billion by 2030.

That trend might not have yet reached a fancy restaurant in Mumbai or Bengaluru but there are ventures like The Boochi Project in India taking six-legged baby steps into that brave new world.

Tansha Vohra who runs it tells me there are over 200 edible insects in India, and a start-up called Insectify is trying to use black fly larvae, which is super high in fibre, for animal food. “We’re in the process of making a miso out of black fly larvae,” she says.

In October this year, India announced its intention to build Maitri II, the country’s newest research station in Antarctica and India’s fourth, about 40 forty-odd years after the first permanent research station in Antarctica, Dakshin Gangotri, was established. The Hindu talks to Dr Harsh K Gupta, who led the team that established it

How do you create a Christmas tree with crochet? Take notes from crochet artist Sheena Pereira, who co-founded Goa-based Crochet Collective with crocheter Sharmila Majumdar in 2025. Their artwork takes centre stage at the Where We Gather exhibit, which is part of Festivals of Goa, an ongoing exhibition hosted by the Museum of Goa. The collective’s multi-hued, 18-foot crochet Christmas tree has been put together by 25 women from across the State. “I’ve always thought of doing an installation with crochet. So, we thought of doing something throughout the year that would culminate at the year end; something that would resonate with Christmas message — peace, hope, joy, love,” explains Sheena.