The Tram Trail

The Hindu

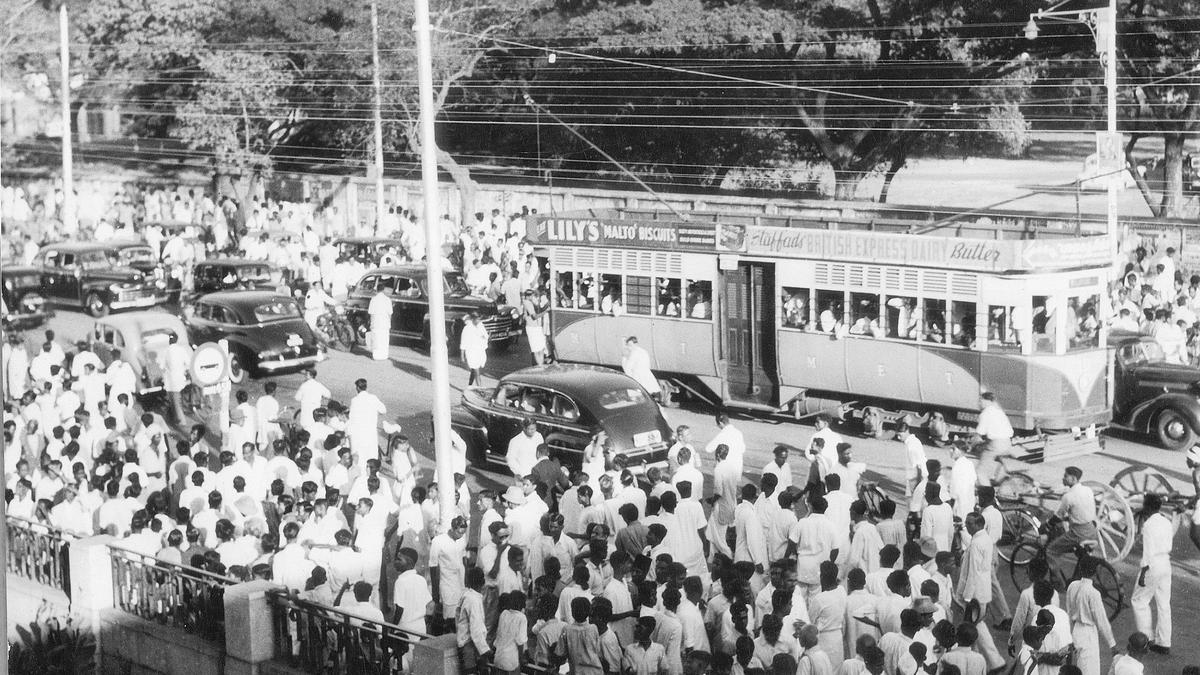

The rise and fall of the Madras Electric Tramway Company, a historical tale of public transport in Chennai.

The Madras Electric Tramway Company is one of those what-ifs that keep cropping up when the city’s public transport infrastructure is discussed. What if, like Kolkata, the tramways had been allowed to continue? But it would seem that the MET was more or less doomed from the start and continued inexorably in that direction, rather like one of those Greek tragedies, until that fateful day in April 1953 when operations ceased, forever. It was marred from start by conflicts between officialdom and the private ownership of the tramways.

And yet, when planned, it was welcomed as a boon to the city. The Hindu in its archives has details from the planning stage itself. It was on March 30, 1885, that the paper reported first on the service. The Commissioners of the Corporation had granted the Madras Tramway Company the concession to operate tramlines within the municipal bounds. The MTC was floated in London with a capital of 185,000 GBP and it planned 18 miles of tramway in the city, running on steel rails and pulled by horses. The MTC had suggested steam power as more economical, but the Commissioners had objected, which marks the first of the clashes and so horses had to be resorted to.

There were enormous delays in the laying of tracks, chiefly because the main roads were all declared out of bounds by the administration. The MTC would have preferred tramlines on Beach Road and in front of Fort St. George but none of this was sanctioned and the lines had to be laid via all kinds of side streets. Four years later, the project was still in the planning stage and in 1889 we learn that the “Madras Tramways Order is to come into force at once” and details of six lines were given, all around George Town, Purasawalkam, Mount Road, Chintadripet and Royapettah. The Local Administration reserved unto itself the right to decide fares – not exceeding half an anna per mile for second class and one anna for the first.

By this time however, it would appear that the Commissioners of the Corporation had changed their minds on the means of locomotion. Perhaps they were reflecting on how the earlier horse-drawn system of trams in the city, which had existed in the 1870s, was an absolute failure. And so ‘mechanical or any other means of power’ was now permitted. The Madras Electric Tramway Company came into existence in 1892 as India’s first and by 1904, after many trials and tribulations including several changes in ownership, the service stabilised as the Madras Electric Tramways (MET), operating as the name suggests, on electric power. This was initially by underground cable and later by pantograph.

There was huge civic pride in the trams and it was exalted in prose and poetry. More importantly, as Stephen P. Hughes points out, it dictated the spots where public entertainment venues came up, and the cinema theatre map of Madras was the result.

But all was not well. In 1917, JF Jones, Chief Engineer of the MET, in a deposition before the Industrial Commission, said that but for “the obstinate attitude of the Madras Government, Madras by this time would have had a better system of tram service”. It is a lengthy statement, supported by an editorial of The Hindu and the gist of it still remained the lack of permission to operate on main roads and a firm hand on the fares.

The MET, with whatever means that were available to it, invested periodically in rolling stock but it found the going increasingly tough. It was a hotbed of labour activism in the 1920s and during one such strike, the MET introduced buses to the city. These were withdrawn once the strike was called off, but private bus operators had seen the potential and from then on, buses were here to stay.