The story of how the deadliest virus to humans was revived Premium

The Hindu

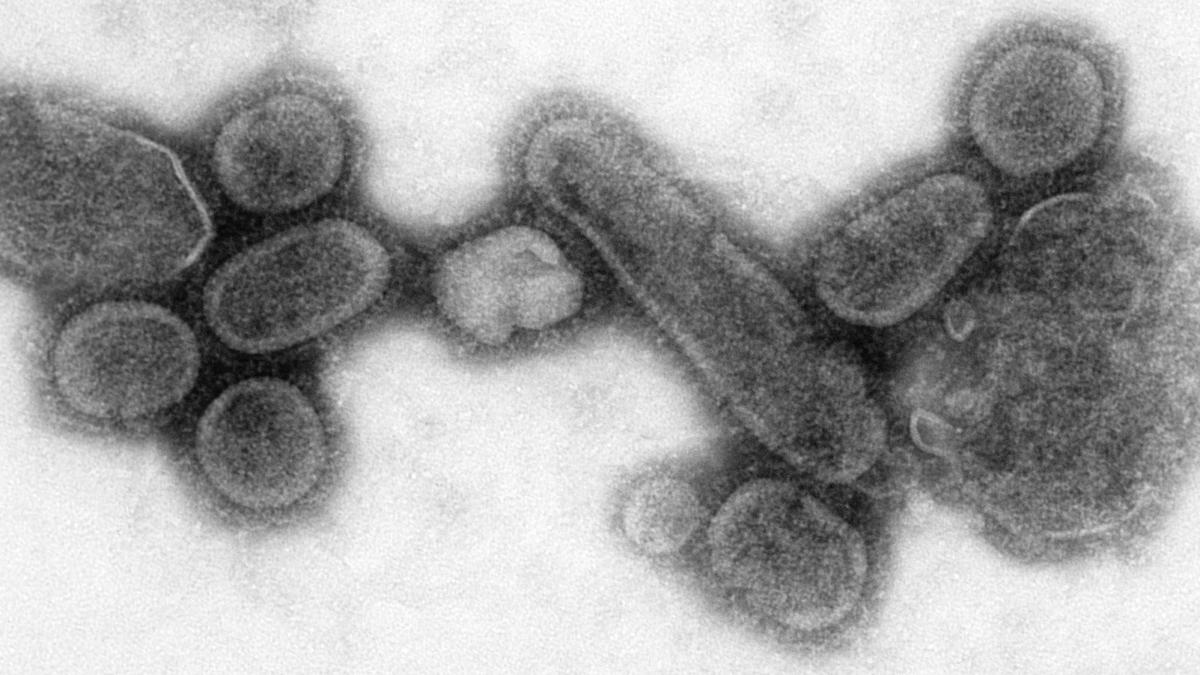

In Aug 1997, Johan Hultin requested permission to exhume a mass grave in Alaska, hoping to find the recipe for the deadliest virus ever known: the 1918 Spanish flu. Scientists routinely engineer viruses, but need nature to create them first. Jeffery Taubenberger wanted to understand why some flu strains caused pandemics, so he sought the genetic makeup of the 1918 strain. Hultin offered to retrieve samples from the mass grave, risking his life, and the samples allowed Taubenberger to determine the virus' full genetic sequence.

This is part I of a two-part story on the Spanish flu virus. Part II will be published tomorrow.

In August 1997, the members of the village council of a small settlement in Alaska, called Brevig Mission, were faced with a peculiar request. A man named Johan Hultin wanted their permission to exhume a nearly 80-year-old mass grave. He claimed that he had done it before, 46 years earlier, and that he was back because his previous mission had failed.

The council gave him its blessing when its members heard what he was after. According to him, hidden beneath the frozen ground lay preserved the recipe to make the deadliest virus humankind had ever encountered.

Scientists routinely engineer new viruses in the laboratory. They make changes to the genetic material (DNA or RNA) of existing viruses to create new variants that may or may not exist naturally. Doing so allows scientists to compare the properties of the edited variants to their natural counterparts and infer the role of the changes that they made.

For example, if they observe that some patients have a higher viral load in their blood for a given disease, and a particular mutation is observed in the DNA of viruses isolated from those patients, they can introduce that mutation into the DNA of viruses that don’t naturally harbour it, to see if it improves the viral output in the laboratory.

But while scientists can easily introduce changes to the genetic material of a virus, they can’t create a virus from scratch. They have to rely on nature to do this.

So, scientists take samples from patients, make more copies of the genetic material using a technique called a polymerase chain reaction, and use it to understand the sequence of bases that makeup its genetic material. Once they have the sequence, they can tweak it.