Scientists make strange 2D metals sought for future technologies Premium

The Hindu

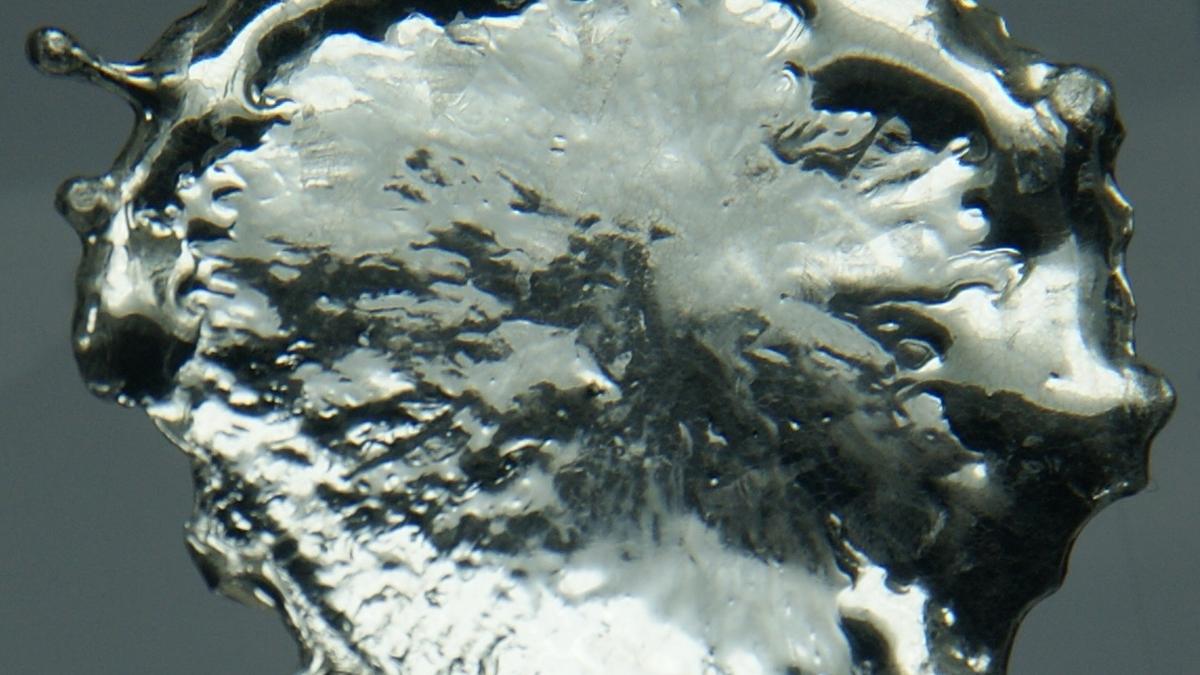

Discover how scientists created 2D bismuth sheets with unique properties, paving the way for next-gen technologies.

A quantum dot is a type of semiconductor that’s only a few nanometres wide. It has a wide range of applications, including in LED lighting, medical diagnostics, printing, semiconductor fabrication, and solar panels. They’re very small but they’ve had a big impact on our world as we know it. This is why the people who found a quick, reliable way to make quantum dots were awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2023.

Quantum dots get their curious but powerful abilities from a phenomenon called quantum confinement. When you throw a switch, a bulb comes on. This is because electrons flow from a power source to the bulb through copper wires. Because the wires are fairly thick (from an electron’s perspective) and very long, the electrons aren’t tightly packed in and move freely. But in a quantum dot, there isn’t much space and the electrons are relatively more close to each other. So even though they’re free to move around the entire quantum dot, and not be confined to their atoms, their movement is still restricted.

In this situation, the amount of energy each electron can have changes. In a copper wire in your house’s circuit, if an electron gains some extra energy in some way, it can simply move around faster. But in a quantum dot there’s nowhere to go, so the electrons can’t simply acquire more energy even if, say, you increase the voltage on the dot. Instead, the electrons can have only specific amounts of energy each. This is exactly how electrons in an atom behave: they have limited energy levels. It’s like they’re in a movie hall. The copper-wire electrons are free to fill any seats they like. But in an atom, some rows are closed off and in the other rows, only specific seats are available. Because all the electrons in a quantum dot behave in this way, the dot itself behaves like a giant atom.

The restrictions the electrons feel because they’re so packed in is said to be due to quantum confinement. A material is described as 1D or 2D depending on how much it confines its electrons. A quantum dot is considered to be a zero-dimensional material: while its electrons can technically move in three dimensions, the volume available is so small that it might as well be a point in space.

Likewise, graphene is a famous 2D material: it consists of a single sheet of carbon atoms bonded to each other in a hexagonal pattern. The electrons in this sheet can only move around in two dimensions, thus 2D. As a result they behave as if they don’t have mass, for example, giving rise to properties not seen in other materials.

The unusual material properties quantum confinement gives rise to are clearly of great real-world value. This is why scientists have also been trying to create 2D metals — but they’ve been running into a thorny problem.

If one graphene sheet is placed above another, the two sheets will develop weak links between them called a van der Waals interaction. They’re very weak bonds: they can keep the sheets from drifting apart but if you tug even one sheet just a little, the interaction will break and allow the sheets to be separated.

In October this year, India announced its intention to build Maitri II, the country’s newest research station in Antarctica and India’s fourth, about 40 forty-odd years after the first permanent research station in Antarctica, Dakshin Gangotri, was established. The Hindu talks to Dr Harsh K Gupta, who led the team that established it

How do you create a Christmas tree with crochet? Take notes from crochet artist Sheena Pereira, who co-founded Goa-based Crochet Collective with crocheter Sharmila Majumdar in 2025. Their artwork takes centre stage at the Where We Gather exhibit, which is part of Festivals of Goa, an ongoing exhibition hosted by the Museum of Goa. The collective’s multi-hued, 18-foot crochet Christmas tree has been put together by 25 women from across the State. “I’ve always thought of doing an installation with crochet. So, we thought of doing something throughout the year that would culminate at the year end; something that would resonate with Christmas message — peace, hope, joy, love,” explains Sheena.