Scientists have detected the largest black hole merger yet. What it is and why it matters

CBC

It was a bump in the night. A big one.

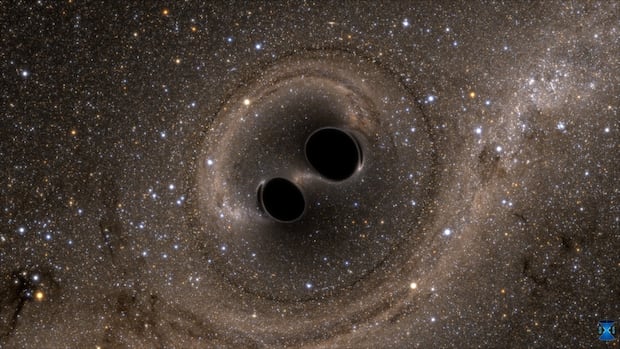

On Nov. 23, 2023, waves from a colossal merger of two black holes reached Earth and were picked up by the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration, a group that detects these sort of mergers through gravitational waves.

And these black holes were chunky, coming in at 100 and 140 times the mass of the sun.

But the final merger produced something even more impressive: another black hole that is more than 225 times the mass of the sun, astronomers revealed today.

Astronomers are excited about this merger because it's unusual. Most of these kinds of mergers detected thus far through gravitational waves have been between 10 and 40 times the sun, said Sophie Bini, a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech who is part of the group.

"We detected the first gravitational wave 10 years ago, and since then, we have already found more than 300 events. So it's really an exciting [time]," Bini said. "But this event in particular is very interesting because it's the most massive one."

Gravitational waves are ripples in space-time that can only be detected by extremely sensitive instruments, like the ones from the collaboration, which are located across the United States, Japan and Italy.

The first gravitational wave was detected in 2015 and announced by astronomers in 2016.

The other interesting discovery of this detection — called GW231123 — is that the pair appear to have been spinning extremely quickly.

"The black holes appear to be spinning very rapidly — near the limit allowed by [Albert] Einstein's theory of general relativity," Charlie Hoy at the University of Portsmouth said in a statement. "That makes the signal difficult to model and interpret. It's an excellent case study for pushing forward the development of our theoretical tools."

Not all black holes are created equal.

There are supermassive black holes that can be tens of thousands to billions of times the sun's mass and lie at the centre of galaxies. The Milky Way, for example, has a black hole at its centre, called Sagittarius A* — or Sgr A* — that is roughly four million times the mass of the sun.

Then there are stellar-mass black holes, which can be from a few times the mass of the sun to tens of times the mass. Or, some argue, a hundred of times its mass. These form when a massive star runs out of fuel and explodes in a spectacular fashion, an event called a supernova.

But then there are those that lie somewhere in between the two, called intermediate black holes. Finding these in-betweens has proved difficult for astronomers. This new merger lies within what astronomers call the "mass gap" between stellar-mass and supermassive black holes.

Nuclear fusion milestones from Canada's General Fusion and China's EAST reactor have caused a buzz over this potentially limitless, clean energy source becoming a reality amid rising power demand from AI and electrification. Meanwhile, new fusion startups have been popping up around the world and have drawn billions in private investment.