Scientists devise ‘glowscope’ to bring fluorescent microscopy to schools Premium

The Hindu

Students and researchers in resource-poor labs can use Foldscopes and ‘glowscopes’ to reveal more about the microscopic world.

In 2014, a group of scientists at Stanford University released Foldscope, a handheld microscope made almost entirely out of paper, which takes 30 minutes to put together, and which could capture images of cells. So far, millions of people – especially schoolchildren – around the world have taken images of the microscopic world with Foldscopes, while dozens of scientific studies have been conducted with the help of this instrument. Its cost? Rs 400.

Foldscope democratised the world’s access to optical microscopy. Now, researchers at Winona State University, Minnesota, have created a design for a ‘glowscope’, a device that could democratise access to fluorescence microscopy – at least partly so.

An optical microscope views an object by studying how it absorbs, reflects or scatters visible light. A fluorescence microscope views an object by studying how it reemits light that it has absorbed, i.e. how it fluoresces. This is its basic principle.

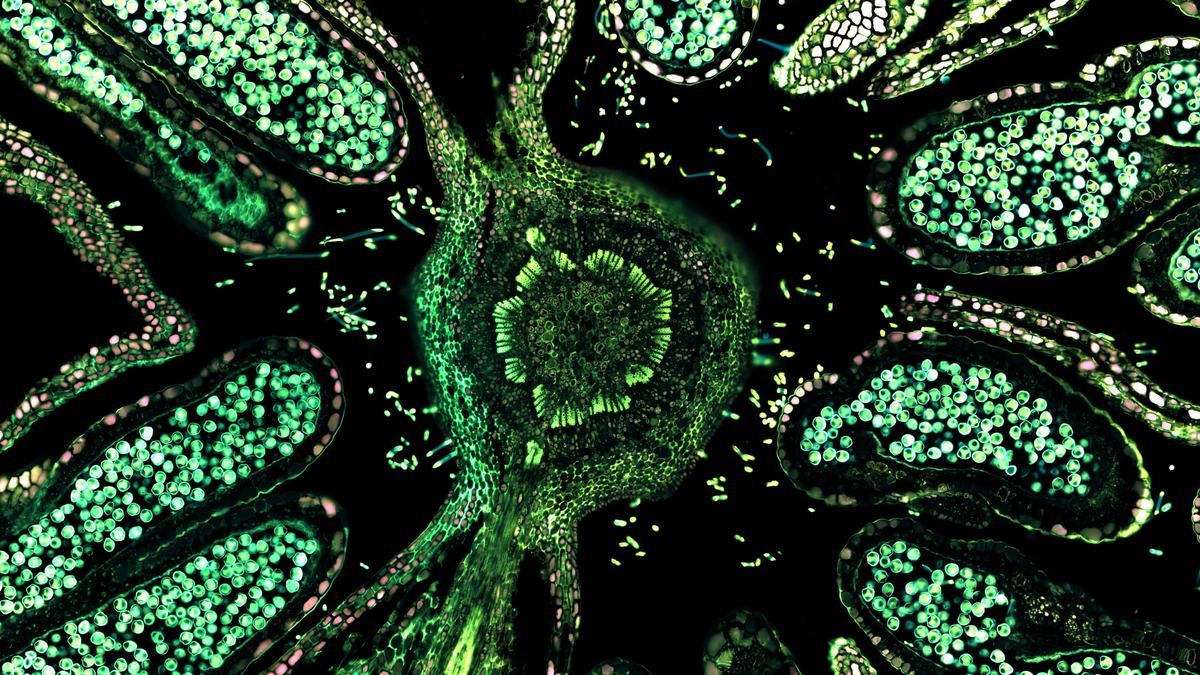

The object is illuminated with light of a specific wavelength. Particles in the object absorb this light and reemit it at a higher wavelength (i.e. different colour). These particles are called fluorophores; the object is infused with them before being placed under the microscope.

There are versions of fluorescent microscopes with more sophisticated abilities, such as epifluorescence and confocal laser-scanning microscopes.

When the fluorophores fluoresce, a fluorescent microscope can track them as they move inside the object, revealing the object’s internal shape and other characteristics. For example, a fluorophore called the Hoechst stain binds to DNA and is excited by ultraviolet light. So a tissue sample collected from a person could be injected with the Hoechst stain and placed under a fluorescent microscope. When the sample is illuminated by ultraviolet light, the stain absorbs the light and reemits it at a higher wavelength. The microscope will point out where this is happening: in the nuclei of cells, where DNA is located. This way, the nuclei in the tissue can be labelled for further study.

Scientists have developed different fluorophores to identify and study different entities, from specific parts of DNA to protein complexes. On the flip side, fluorescence microscopes cost at least a lakh rupees, but often up to crores.

Max Born made many contributions to quantum theory. This said, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 1954 for establishing the statistical interpretation of the ____________. Fill in the blank with the name of an object central to quantum theory but whose exact nature is still not fully understood.