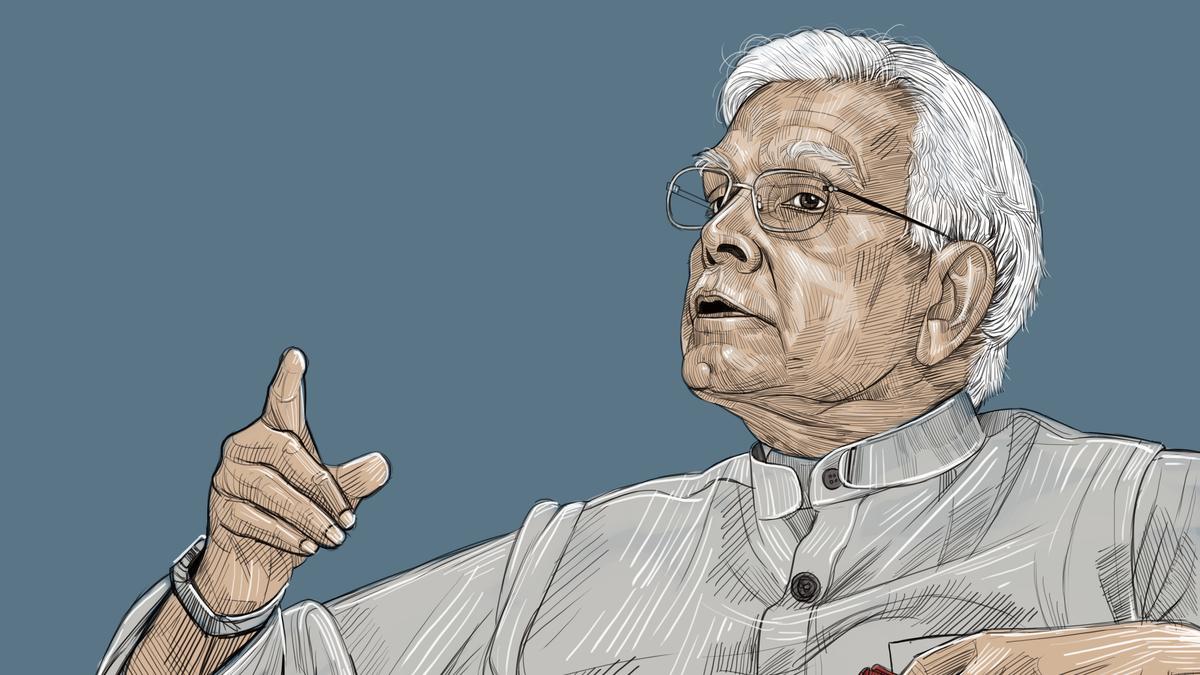

Natwar Singh: Nehruvian, memorist, friend

The Hindu

A journalist-turned-friend remembers Natwar Singh the diplomat (1929-2024) who loved his books and tea time conversations, and stood by his political ideals

Natwar returned to his favourite place, his farmhouse outside Delhi, for one last time on August 10. It was here that he had summoned me in the summer of 2011. At the end of our conversation, he reached out to his magnificent collection of books and gifted me a copy of A Bunch of Old Letters, one of the last books by Jawaharlal Nehru. The letters gave a glimpse of Nehru’s career as well as the world that greeted K. Natwar Singh as he started a career that would span the prime ministerships of Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, and Manmohan Singh. Letters helped him remember the past.

Last year, he recollected his first and only meeting with Mahatma Gandhi. His father, one of the three Nazims of Bharatpur, was not fond of the leader. Bharatpur’s royal house was one of the several princely states that were intimidated by the Mahatma. News had spread, and thousands of people had gathered at the train station to get a glimpse of Gandhi. Natwar said that perhaps as a polite gesture to the sentiment of the princely state, Gandhi declined to step out of the railway compartment and stayed inside.

Teenaged Natwar was determined to speak to Bapu and zigzagged within the crowd. Not to be disappointed, he jumped onto the track, went to the other side of the compartment, grabbed the edge of the window, and pulled himself up. Once there, he could see Gandhiji, bent over and reading. A sea of humanity had surrounded the train, but that did not disturb the Mahatma who appeared serene. Natwar looked at the Mahatma but did not get any response as he was in the middle of one of his many silent penances.

Natwar first narrated this story over a phone call and then during our next meeting. As the story came to depicting how Gandhiji was seated, Natwar shrunk his shoulders draped in a white shawl to show the exact posture. As he narrated, he painted a vivid picture with his words and body language — of the environment on the railway platform, the crowd, young Natwar and even his restless father at home looking for his son who, despite his disapproval, had decorated his room with photos of the leaders of the nationalist movement. Such was the power of narration and memory that Natwar possessed.

I once asked him about the trick behind it. He was quick with the answer: “We did not have all these gadgets that you have. Whatever we read had to be memorised. There was no other way.”

Like many of the figures of Natwar’s growing up years, he too became a figure who found space on newspaper pages. Long before our tea time talks became a monthly feature, I was introduced to him through these pages. He was a minister of state for external affairs in my childhood. His ministerial stint came to an end with the end of the Rajiv Gandhi government in 1989. During the P.V. Narasimha Rao years, he was in partial political exile as Rao and he did not see eye to eye. Natwar was a Nehruvian and too much of a non-alignment oriented figure. He launched the Indira Congress with N.D. Tiwari.

In 2005, I was with The Week magazine and Natwar was again in the news. He was the external affairs minister and was being accused of being a beneficiary of the oil-for-food payments that was rocking the western headlines. He gave a brief telephonic interview. A few days later, his secretary called me to a meeting with the minister. Natwar arrived dressed in a spotless white kurta pajama. Our meetings continued even after he quit the cabinet post on December 6, 2005. Each meeting would include cups of tea and sometimes, a meeting would turn into a round table with a few other guests and his wife Heminder Kumari Singh joining in.

How do you create a Christmas tree with crochet? Take notes from crochet artist Sheena Pereira, who co-founded Goa-based Crochet Collective with crocheter Sharmila Majumdar in 2025. Their artwork takes centre stage at the Where We Gather exhibit, which is part of Festivals of Goa, an ongoing exhibition hosted by the Museum of Goa. The collective’s multi-hued, 18-foot crochet Christmas tree has been put together by 25 women from across the State. “I’ve always thought of doing an installation with crochet. So, we thought of doing something throughout the year that would culminate at the year end; something that would resonate with Christmas message — peace, hope, joy, love,” explains Sheena.

Max Born made many contributions to quantum theory. This said, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 1954 for establishing the statistical interpretation of the ____________. Fill in the blank with the name of an object central to quantum theory but whose exact nature is still not fully understood.