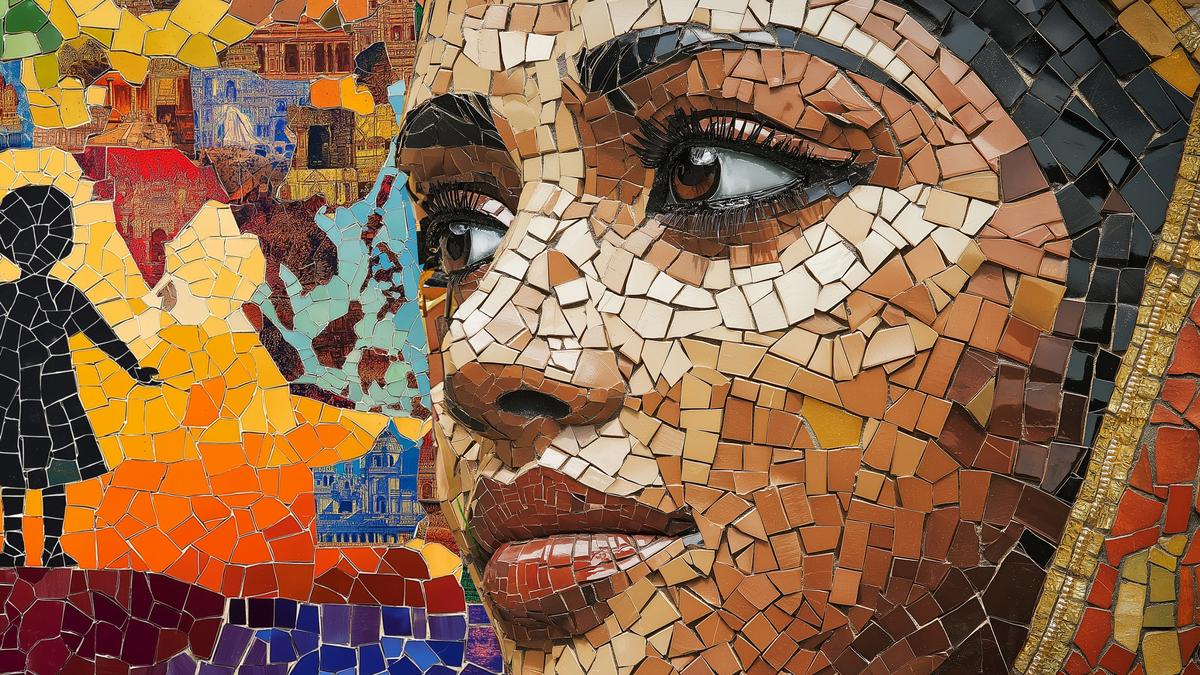

Independence Day 2024 | India’s ‘mosaic’ children

The Hindu

Exploring the complexities of identity, belonging, and migration in a diverse world through personal stories and reflections.

Over the past year, I have come across several headlines in news reports that reference communities based on linguistic boundaries: ‘Malayali trekker stranded in…’, ‘Telugu man competing in…’, ‘Punjabi woman killed…’.

My son is half-Tamil, half-Malayali, but fully from Delhi, in his own uncomplicated mind. In my overthinking brain, I wonder, if he ever makes it to a headline (hopefully, a happy one), how he will be ‘classified’, which community will ‘claim him’. In an opportunistic world, if it’s good news, possibility both will.

Like Thulasendrapuram, the village in Tamil Nadu that is praying for Kamala Harris to become President of the United States, even though no one from her family still lives there. At a rally recently in Montana, Donald Trump, her opponent in the presidential election, asks bizarrely: “You know it’s interesting: nobody really knows her last name.” Then, “Harris, it’s like Harris. I don’t know how the hell did this happen.” It happened because she has an Indian mother and a Jamaican father. And on another occasion, “I don’t know, is she Indian or is she black?” It didn’t occur to him she could be both.

Life is simple when you have a single-place identity, meaning if your parents are from a particular area, you speak that language at home, and you’ve grown up there. Our identities get complicated when we are migrants; our sense of belonging turns into longing, when we have been exiled or cut off from our place of birth; when our homes are not really where our hearts are.

A large influence on where people live and move to is politics and policies. This month, in an enforcement of the straight and narrow, Himanta Biswa Sarma, who on social media ironically announces himself first as a citizen of India before Chief Minister of Assam, said that a new domicile policy would be implemented, making only those born in the State eligible for government jobs.

Similarly, last month, the Karnataka State Employment of Local Candidates in the Industries, Factories and Other Establishments Bill, 2024, mandated reservation for local candidates in 50% of management positions and 70% of non-management positions in private-sector jobs. Proficiency in Kannada was one of the criteria to define ‘local candidate’. The bill faced a massive push-back from industry and was temporarily put on hold. Migrants, after all, are the brick-and-mortar, the brains-and-muscle, of many cities.

When someone asks Uma Ganju where she’s from, she says, “Srinagar,” and for people internationally, “Srinagar, in Kashmir.” Because, “there is always a follow-up question about the trouble there. Maybe it is my way of letting the world know that there’s this place where all is not well”. Her family left much before the 1989 insurgency, for jobs in other Indian cities, but, “One day in Delhi, my grandparents showed up at our doorstep. My grandmother was in her night clothes, and holding just one bag. My grandfather rarely spoke about Kashmir with us after that. My grandmother would tear up at the mere mention of the place. My aunt and cousins left in the middle of the night in a shared taxi, bundled up with other fleeing Kashmiri Hindus.”

Although students from Tamil Nadu remain the leading recipients of educational loans across India, there has been a significant decline in the number of active loans they hold. The number of active education loan accounts decreased from 27.4 lakh accounts to about 20.1 lakh in the period. The fall can be mostly attributed to the fall in Tamil Nadu’s numbers.