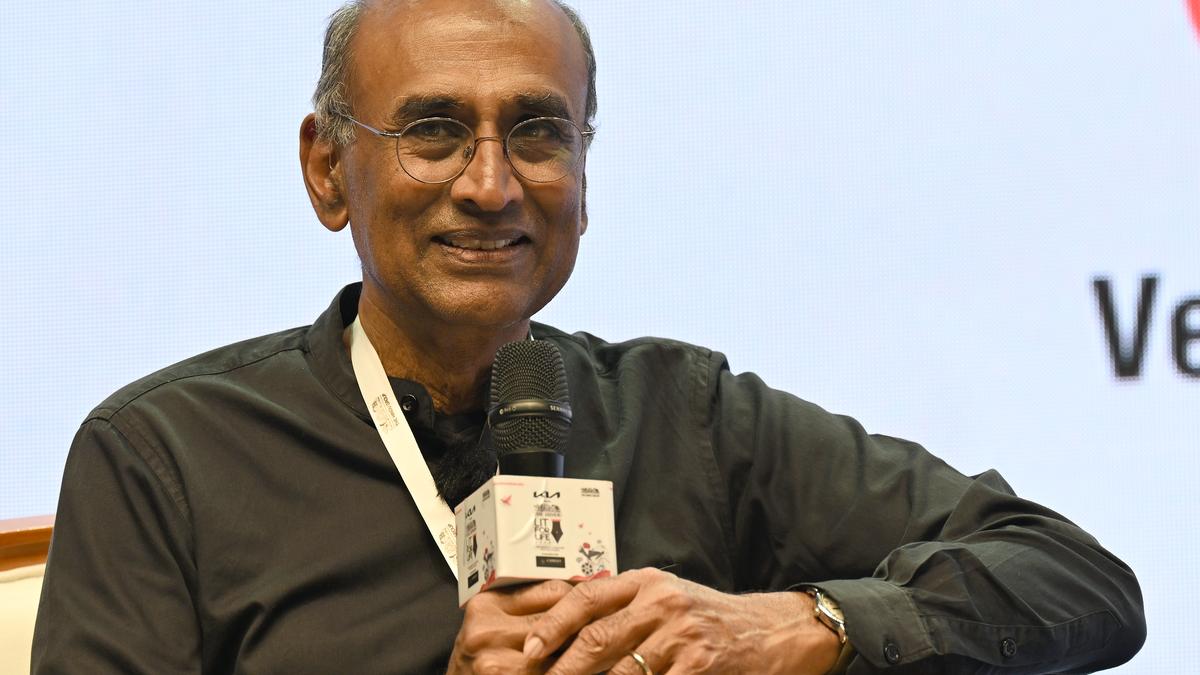

Funding, infrastructure, general environment woes unattractive for senior international scientists to work in India: Nobel laureate Venki Ramakrishnan Premium

The Hindu

U.S. funding cuts prompt scientists to consider moving abroad, with India facing challenges in attracting top talent.

With the U.S. terminating several research programmes, firing thousands of federal scientists, and cancelling important, high-value federal research grants— $8 billion already and further cuts of almost $18 billion next year for National Institute of Health (NIH), proposed cuts of about $5 billion next year to National Science Foundation (NSF), proposed cut of nearly 25% to NASA’s budget for 2026, and billions of dollars cut in grants to several universities — many U.S. scientists are planning to move to other countries.

According to an analysis carried out by Nature Careers, U.S. applications for European vacancies shot up by 32% in March this year compared with March 2024. A Nature poll found that 75% of respondents were “keen to leave the country”.

The European Union and at least a handful of European countries have committed special funding to attract researchers from the U.S. But the committed funding is dwarfed by the scale of funding cuts by the U.S., and the funding is already highly competitive in Europe, senior scientists from the U.S. moving to Europe in large numbers may not happen.

“There will be a few scientists who will move, but I do not see a mass exodus. Firstly, salaries in Europe are well below those in the U.S. Secondly, moving is always difficult both professionally and personally. Finally, the U.S. is still the pre-eminent scientific country, and that will be hard to walk away from. I say this as someone who actually did move from the U.S. to England over 25 years ago, with a salary that was just over half what I was making there,” Nobel Laureate Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, professor at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, U.K., says in an email to The Hindu.

In comparison, India has only a handful of institutions such as IISc, NCBS, TIFR, IISERs and IITs that can possibly attract U.S. scientists. According to him, even the renowned institutions in India are “world class only in some very specific areas”. “I do not see India as a general magnet for international science,” Prof. Ramakrishnan says.

Though funding for science in India has increased in absolute terms, the percentage of GDP allocated to R&D has actually reduced. India’s gross expenditure on R&D is estimated to be around 0.6-0.7% of GDP in 2025. Specifically, with long-term assured funding for basic research, which is an absolute necessity to attract researchers based in America, not guaranteed by existing programmes, can India take advantage of the situation in the U.S.? “India’s R&D investment as a fraction of GDP is much less than China’s and is about a third or less of what many developed countries have, and far below countries like South Korea. It will not be competitive without a substantial increase,” he says.

About funding in general and funding for basic research in particular, Prof. Ramakrishnan says: “Neither the funding, the infrastructure nor the general environment in India is attractive for top-level international scientists to leave the U.S. to work in India. There may be specific areas (e.g. tropical diseases, ecology, etc) where India is particularly well suited, but even in these areas, it will be easier for scientists to do field work there while being employed in the West.” Given a choice between some European country or India, he strongly vouches Europe as “far more attractive as a scientific destination”.

Discover the all-new Kia Seltos 2026 – a refreshed C-SUV that combines premium design, advanced technology, and class-leading comfort. Explore its redesigned exterior with the signature Digital Tiger Face grille, spacious and feature-packed interior, multiple powertrain options including petrol and diesel, refined ride quality, and top-notch safety with Level 2 ADAS. Find out why the new Seltos sets a benchmark in the Indian C-SUV segment.