A memory palace for loss | Review of Geet Chaturvedi’s Simsim, translated by Anita Gopalan

The Hindu

A poetic and evocative translation capturing the essence of space, time, and memory in Geet Chaturvedi's Simsim

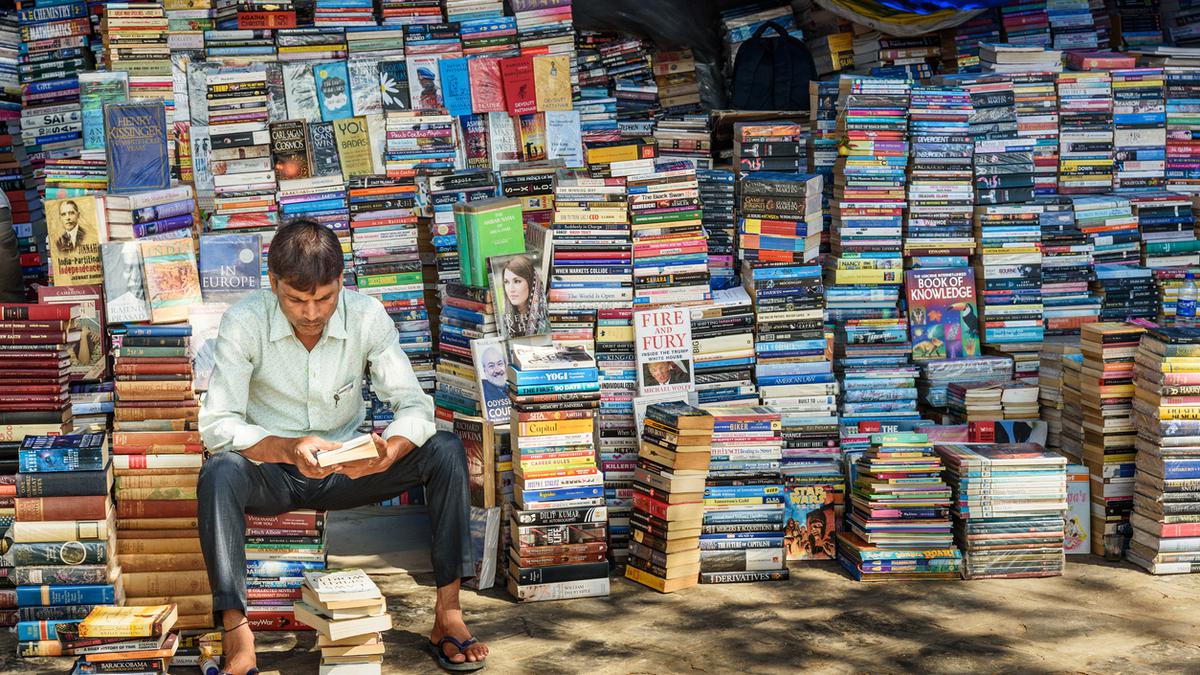

The voices that mainly inhabit Simsim — Hindi poet and author Geet Chaturvedi’s new translation, longlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature 2023 — belong to Basar Mal Jetharam Purswani, the aged proprietor of a library that has seen better days, and the unnamed student who often walks through the tiny lane where the library is located.

On most days, doddering Basar Mal fights damp, dust, the land mafia that threatens to destroy his library, and the ravages of age which continually efface memories of his beloved and his homeland. Meanwhile, his wife, for want of a child, adopts a doll and devotes the remainder of her days to its care. The unnamed student who walks by the library begins to imagine a young girl who appears at a specific window and vows to make her his beloved. He imagines their life together while escaping arguments with his father on how to build his career. The other prominent voice in the story is that of a book that talks about the politics of language and gender while revealing why book burnings have existed throughout history.

What Chaturvedi manages to accomplish through Simsim is a capturing of the essence of space and time. Basar Mal’s childhood in Sindh, the horrors of Partition, migrating to a foreign land, each is evoked not through narration or description but through the lightness of everyday prose and interactions.

Chaturvedi manages to make the reader feel what his characters are going through. To achieve this wonderful effect, he uses a variety of literary forms, including poetry, philosophical rumination, even magical realism. But in doing so, he also rather subtly further blurs the lines between reality and memory, not just for his characters but his readers as well.

The author builds his characters through the most commonplace interactions in everyday situations. When Basar Mal is asked to show proof of being a Sindhi refugee, he simply states the only proof he has is that he can speak Sindhi. When he goes around looking for jobs, he’s told to seek employment from Jinnah. Basar Mal’s library becomes a memory palace for displaced Sindhis. It is through their sharing of loss that we truly understand the horror of what has befallen them. In Chaturvedi’s prose, the everyday ordinary becomes extraordinary.

In the deft hands of Anita Gopalan, the translation carries through the author’s intentions of being revelatory, prophetic and yet always mellifluous. There is a lightness that mirrors the sensory triggers of memory for Basar Mal, and once the memories fade, all that remain are their smells. Chaturvedi and Gopalan’s work is indelible, in that it cannot be truly forgotten.

The reviewer is a freelance writer and illustrator.